How do you tell when it’s time to deprecate a system? If something mostly works OK, is it worth spending time and effort replacing its functionality?

At Artsy, we realized several years ago that we needed to be able to group a bunch of artworks together. If we wanted to have a page with all of the ceramics by Lucio Fontana, or contemporary prints from the IFPDA Fair Sprint 2022, or a gift guide curated by Antwaun Sargent, we needed to have a way to make that happen.

We decided to call these things “collections,” a reasonable name for a collection of artworks. In order to create them, we developed a service called KAWS, named after the artist (whose works we wanted to put in several of these collections).

Now, 4 years later, we’ve taken down the service and folded its functionality into Artsy’s main database and API, Gravity.

Let’s talk about why and what we learned along the way.

A little context

KAWS has a somewhat unusual design. It’s a server, a Node.js app with its own Mongo database, and it serves up a GraphQL API. It also relies on TypeORM to map TypeScript models to database records and TypeGraphQL to keep TS and GraphQL types in sync.

This makes it a bit different from most services Artsy maintains. Most of our APIs are Ruby on Rails apps, and we don’t have any other uses of TypeORM and TypeGraphQL. When it was created, it was a cool experiment with a possible direction for future APIs - one we decided not to pursue for the time being.

KAWS doesn’t store any artworks - or even any artwork IDs. Instead, it just stores a “query”, a set of Elasticsearch criteria. This could be a list of artist IDs or gene IDs, a tag ID, a keyword, or any combination of those things.

In other words, a KAWS artwork collection could be defined in human-readable terms as something like “artworks with the ‘Black and White’ gene by the artist Bridget Riley” or “artworks by Auguste Rodin with the keyword ‘bronze’ and the gene ‘Sculpture’.”

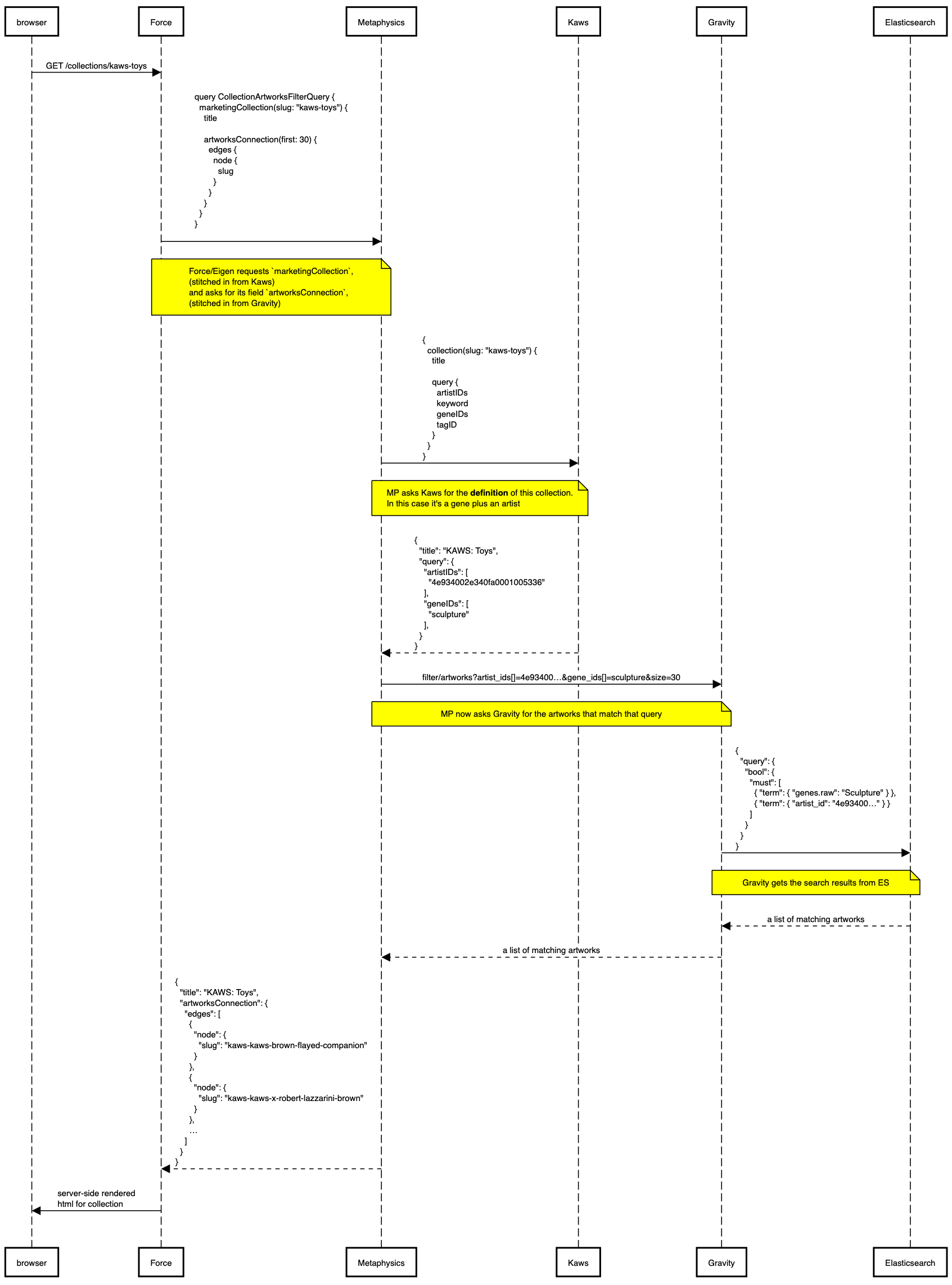

This approach results in a somewhat odd flow for resolving collection requests. Let’s say a user requests the page KAWS: Toys. Our frontend, Force, sends a request to Metaphysics, our GraphQL API.

Metaphysics knows to route that request to KAWS - it asks KAWS “hey, what’s the Elasticsearch query for the

collection with slug kaws-toys? Also, give me the title, the category, the header image, the description text,

and [any other pieces of metadata about the collection itself].” But it can’t ask KAWS for the artworks!

Instead, it receives the query from KAWS and then turns around and sends another request to Gravity, which stores

all of our artworks and indexes them in Elasticsearch so that we can filter them. “Hey Gravity, I got this query

from KAWS (the service, not the artist): { artists: 'KAWS', genes: 'Sculpture' }. Can you return me all of the

artworks that match that query?”

Gravity takes those parameters and passes them to its Elasticsearch cluster, fetching all artworks that match the criteria (and sorting/filtering them according to what the user has selected on the page).

Gravity returns those artworks to Metaphysics, which then packages them up with all of the collection metadata it received from KAWS and returns to the client that requested it. Whew!

Here’s a diagram showing what that looks like:

Why did we decide to deprecate it?

Idiosyncratic stack

As mentioned above, KAWS is an unusual app by Artsy standards. It’s neither a database-backed Rails/Ruby app, nor an API-consuming JavaScript/Node app. It was missing the typical Rails niceties (a dev console, background jobs, rake tasks, etc.), and inclusion of elements like TypeORM and TypeGraphQL that don’t exist in our other apps meant there was a bit of a learning curve for working with it.

While it’s not terrible to have some variety in our systems, it does make them harder to work in and keep up-to-date. And that also resulted in a high…

Lottery factor

There are still people at Artsy who’ve worked in KAWS, but the top 4 contributors have moved on to other companies. That meant that any projects involving KAWS required extra effort to familiarize devs with the system.

Lack of relationship between collections and artworks

Any KAWS-backed artwork grid (e.g. any /collection/:slug page) is the ephemeral result of a canned search query.

This has some advantages: collections stay evergreen & current, so long as artworks with appropriate metadata

continue to land on the platform. But it also has some downsides: there is no modeled relationship between a

collection and its artworks, so given an artwork, you can’t tell what collections it’s in.

Extra hops on each request

Every /collection/:slug request has to go to → MP → Kaws→ MP → Gravity → ES. The diagram above illustrates this

flow. And it’s worth noting that KAWS really doesn’t store that much. It’s a whole service that only stores a

single data type.

Lack of admin UI

Collections in KAWS were first created via a CSV import, then eventually a Google Sheets-driven workflow was added. To create or update a collection, an admin creates/modifies a row in the spreadsheet, then goes to our Jenkins UI and kicks off an “update collections” job, which causes KAWS to pull the new data from the Google Sheet.

This is a pretty rough workflow, and it means it’s very easy to accidentally modify or delete information from a collection (e.g. overwriting the text in the wrong cell).

How did we go about planning it?

This actually wasn’t the first time we attempted to deprecate KAWS. It became something of a running joke: every October for 3 years running (2019, 2020, 2021), someone would say “hey we should probably deprecate this thing” and write a tech plan.

This time, there were three key differences that allowed us to get it done:

-

There was a business need to do it. We want to work on improving collections, bringing new features to them and making it easier for our admins to manage and use collections for important marketing campaigns. We took a look at collections as they existed and said “deprecating KAWS and moving its functionality into Gravity is a prerequisite for these projects.” We could have eventually completed them, but it would have been slower and more difficult - we were confident that investing time into this refactor now would save a lot of time and headaches later.

-

We kept the plan very tightly scoped, focusing only on “maintain existing functionality and move it to Gravity.” Previous iterations of the tech plan had proposed broader changes, such as rethinking collections modeling entirely or breaking with our existing GraphQL schema. Any changes to fields currently being consumed by our frontend clients significantly increases scope, especially since our GraphQL schema is “baked in” to our app. That means that if we removed fields the app was currently relying on, some users who never upgrade their apps would see that functionality break.

To be clear, the authors of those tech plans weren’t wrong to propose rethinking and improving how collections are modeled and served! We may very well end up implementing some of their ideas and suggestions. The learning this time around was mostly “we’re never going to get this done unless we really rein in the scope.”

Our goal was 100% compatibility: all of the currently-used fields would still be available and could be successfully resolved by Gravity instead of KAWS. Even if we changed the type of those fields or updated how they were resolved, they still needed to exist. We did end up getting rid of lots of fields that were not being used by frontend clients (which meant a lot of spelunking through our code and trying to find out if fields like

showOnEditorialwere still being used), so the schema is still significantly simpler and cleaner than it was. -

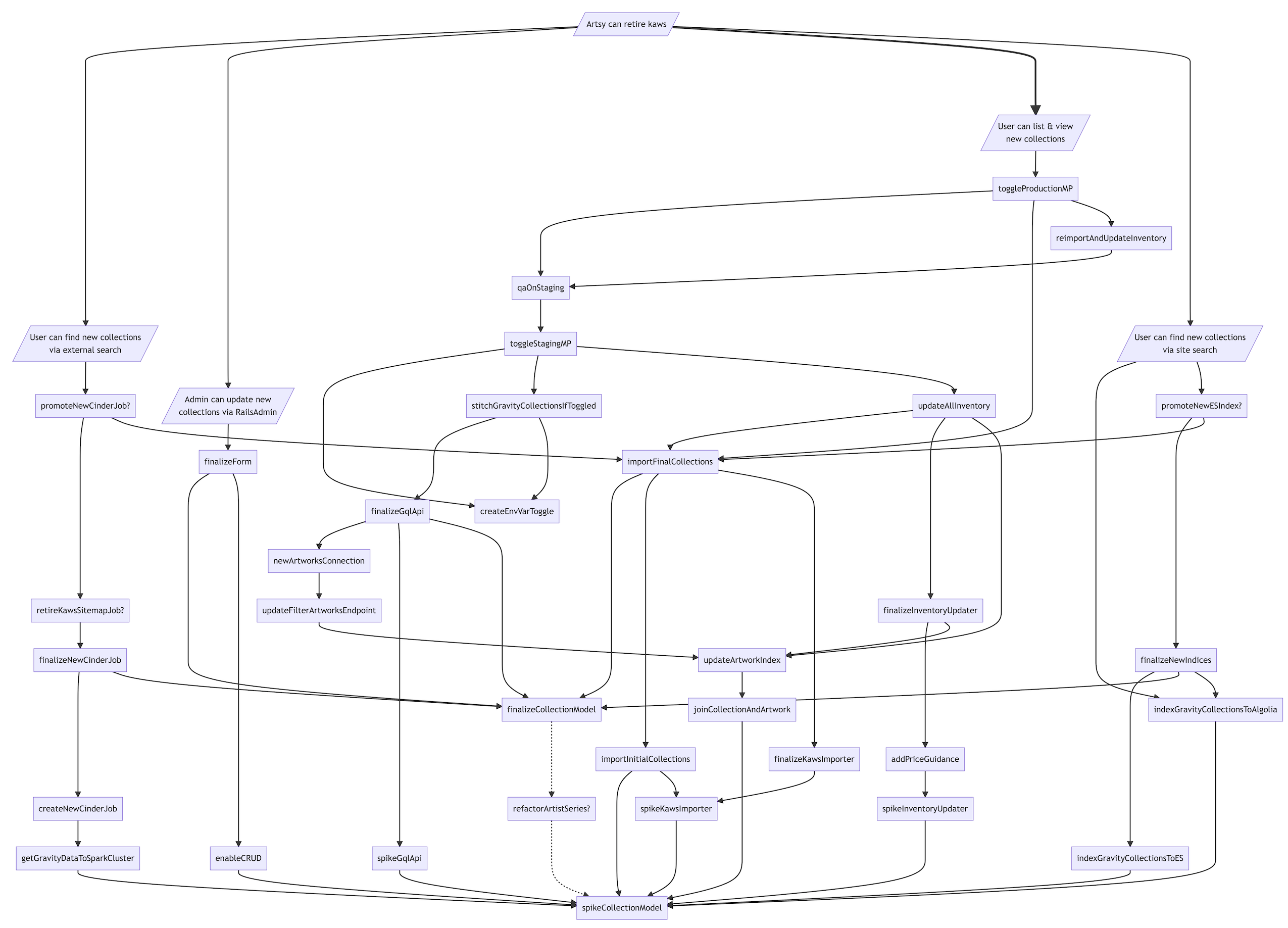

Roop laid a really nice foundation by writing up a thorough document about what KAWS is, how it works, and the steps we might need to take in order to deprecate it. Much of this blog post comes almost verbatim from that document! It’s a testament to the power that well-organized documentation can have: being able to see and understand the problem gave us confidence to tackle it.

Here’s the diagram he created that sketches out how we might go about deprecating KAWS:

What did we learn?

It’s easy for scope to expand without you noticing

I mentioned that our goal was JUST moving KAWS functionality to Gravity, and that we wanted to avoid adding new functionality to keep the project focused. We mostly did that - but we did get off track in one important way.

We’ve discussed how KAWS doesn’t include direct relationships between artworks and collections. As we worked on

moving collections to Gravity, we had a baked-in assumption that there would be a join model between Artwork and

MarketingCollection (the name of the model in Gravity). This was largely informed by the approach we took to

moving ArtistSeries from KAWS to Gravity, a project we previously completed.

In that case, we created an explicit link between the ArtistSeries model and the Artwork model, and we updated

those relationships with a daily recurring job. We would essentially run the query defined by the ArtistSeries,

see if there were any new artworks that matched, and if so, add them to the Series in question.

When we tried this same approach for MarketingCollections, we noticed there was a problem: ArtistSeries cap out

at a few hundred works, but MarketingCollections could be as many as several hundred thousand for collections

like “Contemporary” that are based on very general criteria. The

jobs to associate artworks with MarketingCollections were taking so long that they ate up all of our Sidekiq

resources and prevented other jobs from being executed in a timely manner.

When we took a step back and looked at the problem, we realized that we were getting ahead of ourselves. Yes, we will likely want to directly associate artworks with collections - but there actually wasn’t a clear business reason for doing so. We were just doing it because we were “pretty sure we might need it at some point.”

So to unblock the project, we removed the join models and instead kept a similar approach to what KAWS used

initially: fetching artworks at request time using the Elasticsearch query stored on the MarketingCollection.

There’s a reason we don’t name our projects after artists!

To quote a post about how we name our projects written by our Senior Director of Engineering, Joey:

Choose a code name scheme that isn’t directly related to your technology or business. A flower business using flower names is cute, but breaks down when you want to build a feature that actually is about tulips.

Most of our systems at Artsy are named after scientific concepts. Force, Eigen, Fresnel. This can seem confusing at first, but it means there are not many opportunities for mistaking a system with its data. With a project like this one named after an artist, discussions get confusing quickly! “Yeah, we need to make sure we’re fetching all of the artworks from KAWS. Sorry, not the artworks by KAWS, I actually meant the Warhol collection. But KAWS is the service. Right. Anyway…”

Feature flagging a GraphQL service with a schema is hard

Our plan for launching this change was pretty simple: introduce a new environment variable to Metaphysics and

toggle it when we wanted to QA or launch. Toggling the variable to true and restarting Metaphysics’ Kubernetes

pods would result in a few updates to the schema (removal of all of the unused types that we got rid of) and would

cause requests for collections to be routed to Gravity instead of KAWS.

We figured that we would flip this variable on staging, QA, resolve any issues, and release. We wouldn’t need to flip it off unless we had broken something big by accident; we wouldn’t be in danger of shipping these changes to production since they would exist only in our staging environment and were not checked in to version control.

However, we had forgotten something crucial: Metaphysics has a post-merge step in CI that creates PRs with any schema updates in client services like Force and Eigen, and the schema it ships to those services is pulled directly from staging Metaphysics. It’s not the version of the schema that’s stored in GitHub (which we had carefully avoided changing by not flipping the feature flag), it’s the schema that exists in the staging environment.

In other words, Force (for example) received an updated MarketingCollection type in its schema, which didn’t

exist (and wouldn’t exist until we finished QA and decided to launch) in production Metaphysics schema. Oops.

This also meant we accidentally blocked deploys for a while. Services like Force have a check before they can be deployed to production: “does my copy of Metaphysics’ schema have changes that are not present in production Metaphysics? If so, that probably means deploying me would break something, so go deploy Metaphysics first.”

Because the flag was still set to false on production, the schema updates would never move past staging. We

eventually figured out the problem and flipped the flag to “off”, re-ran the “update client schemas” job, and

deployed Force without the updated schema. But it made for a pretty confusing few hours, and it could have been

bad if we needed to ship an urgent bugfix. Lesson learned.

We ended up creating a Force review app that pointed at a Metaphysics review app with the flag set to true to

avoid causing more issues. This is definitely what we would do next time.

Conclusion

Overall, we’re feeling pretty happy about how this project went. We hit a few snags along the way, but we launched the change earlier this week and haven’t seen any noticeable bugs or problems.

Of course, there’s still an important question: was it worth it? What did we gain by completing this refactor?

The answer will mostly depend on what happens next. We’re meeting with stakeholders next week to talk about what kind of features we can add or modifications we might want to make. But for now, we’re excited to have one less application to maintain and to have made it easier for future Artsy engineers to understand and iterate on our collections infrastructure.