It was a Wednesday, mid-summer 2019. I don’t know which Wednesday specifically, but I know that it was a Wednesday because I was attending Artsy’s weekly all-hands meeting. Two hundred colleagues were also there (many dialing in remotely) and we were all listening to Artsy’s new CEO talk about the company’s direction. Mike Steib had only been around for a few months at that point, getting to know the business. He was talking about the product direction, and I was listening intently.

With Artsy’s iOS app, I knew there were only really two directions we could go. As I listened, I reflected on how we had gotten here.

When I joined Artsy in 2014, I joined the Mobile Team. It was an amazing team. While we were called the “mobile” team, we only worked on Artsy’s iOS apps and not the mobile website.

By 2016, Artsy Engineering had grown to the size that having only a “mobile team” and a “web team” was no longer working well. We dissolved both teams and distributed the engineers into new product teams, focused on vertical aspects of Artsy’s business. Auctions. Partner Success. Editorial. And so on. The idea was that each team would have total autonomy over building products to support their slice of the business, and each would have the engineering and design resources to build new features across both our web and iOS canvases.

That structure worked well, and continues to work well today (we have continued re-organizing ourselves into new teams to better meet business goals). But once we dissolved the mobile team, there was no longer anyone looking at our iOS software holistically. The app had become a series of silos – each silo was internally consistent, but distinct from each other. Often each silo was written in distinct programming languages (we had also started adopting React Native).

New iOS technologies had been created by Apple, but our teams weren’t taking full advantage of them. We would update to support the latest versions of Xcode and iOS in the free time between other tickets. It wasn’t ideal. Of the five original members of the Mobile Team, everyone else had moved on except me.

As a product, the app was languishing.

Yet despite this, it was also hugely popular among our users and very important to Artsy’s business. Art collectors love our app! It gets a large percentage of our total sessions. Also, users place an outsized number of auction bids and artwork inquiries using our app relative to the number of sessions on our website. In fact, the highest value artwork transaction ever to take place on Artsy was made on an iPad, running software that I helped build. I’m still pretty proud of that.

So, Wednesday all-hands. I stood there, not sure of what would happen next. I could see Artsy either making a massive investment in the app, or I could see Artsy cutting its losses and focusing on the software that we already knew how to build. Which direction we took largely depended on this new CEO, who was now standing in front of us all and describing the direction Artsy’s product would take next.

The Dream

Mike said something that caused a lot of raised eyebrows in the crowd. People were excited. I was excited. Artsy’s product organization would shift to adopt a “mobile-first strategy.”

Someone asked “does this mean the app will reach feature parity with Artsy’s website?”

Mike responded: “No. It means that features are going to launch first on the app. If anything, it’s the website that will be catching up to the app.”

I was kind of blown away! I mean, this had been the spirit of our original re-org in 2016, but that hadn’t really materialized. The app had continued to trail the website. At most, only one product team was ever building new features for the app (usually which ever team I happened to be on). Shifting to this mobile-first strategy would be a massive undertaking, but I was keen.

In August, an email landed in my inbox from Artsy’s head of software. He wanted to spin up a new team to focus on the app: the team would be responsible for supporting Artsy’s new mobile-first product strategy. He wanted to know what I thought, and he wanted to know if I was interested in leading the team.

Honestly, it was a dream come true.

Here we are, a year later. This is the story of how Artsy created its Mobile Experience team. How we recovered a languishing iOS app. How engineers helped shift the product organization to a mobile-first product strategy. And how Artsy grew from sometimes having a team working on the app, to usually having every team working on it.

Getting Our Bearings

When Artsy created its new Mobile Experience team, we were already resource-constrained and so the new team would need to be nimble. We had three full-time engineers (myself as tech lead, and two others), assisted by a designer, product manager, and data analyst, who would each be spending only half their work time on the Mobile Experience team. We needed to be scrappy. I’m really proud of the work that that early team accomplished, and I look back fondly on those first few months working with Sam, Joanna, David, Kieran, and Ani.

The first thing we did was define our own mandate. What was this team responsible for? What was it not responsible for? “Mobile Experience” is pretty vague, and we had to answer a lot of upfront questions. Would we be responsible for all of Artsy’s iOS software? No, just the main collector app. Would we be responsible for Artsy’s mobile website? No, that’s too far-reaching. What about Android? Well, yes, eventually…

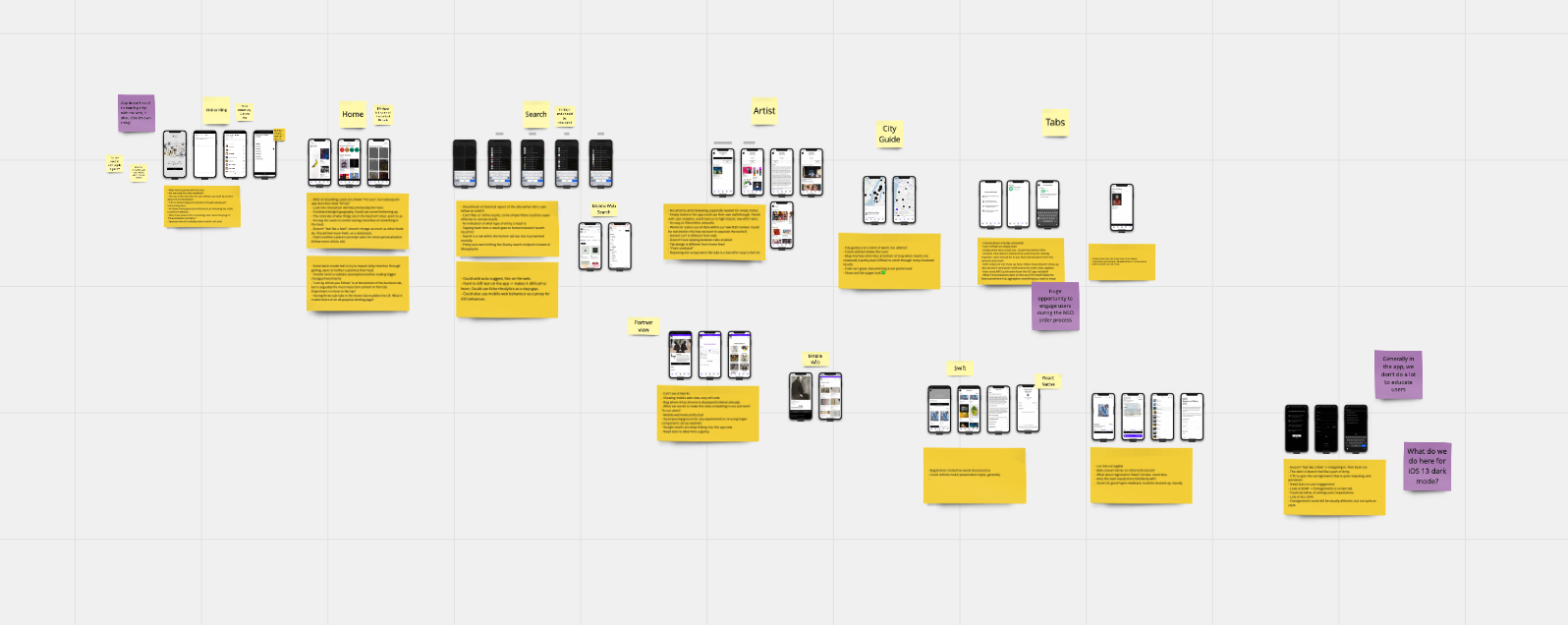

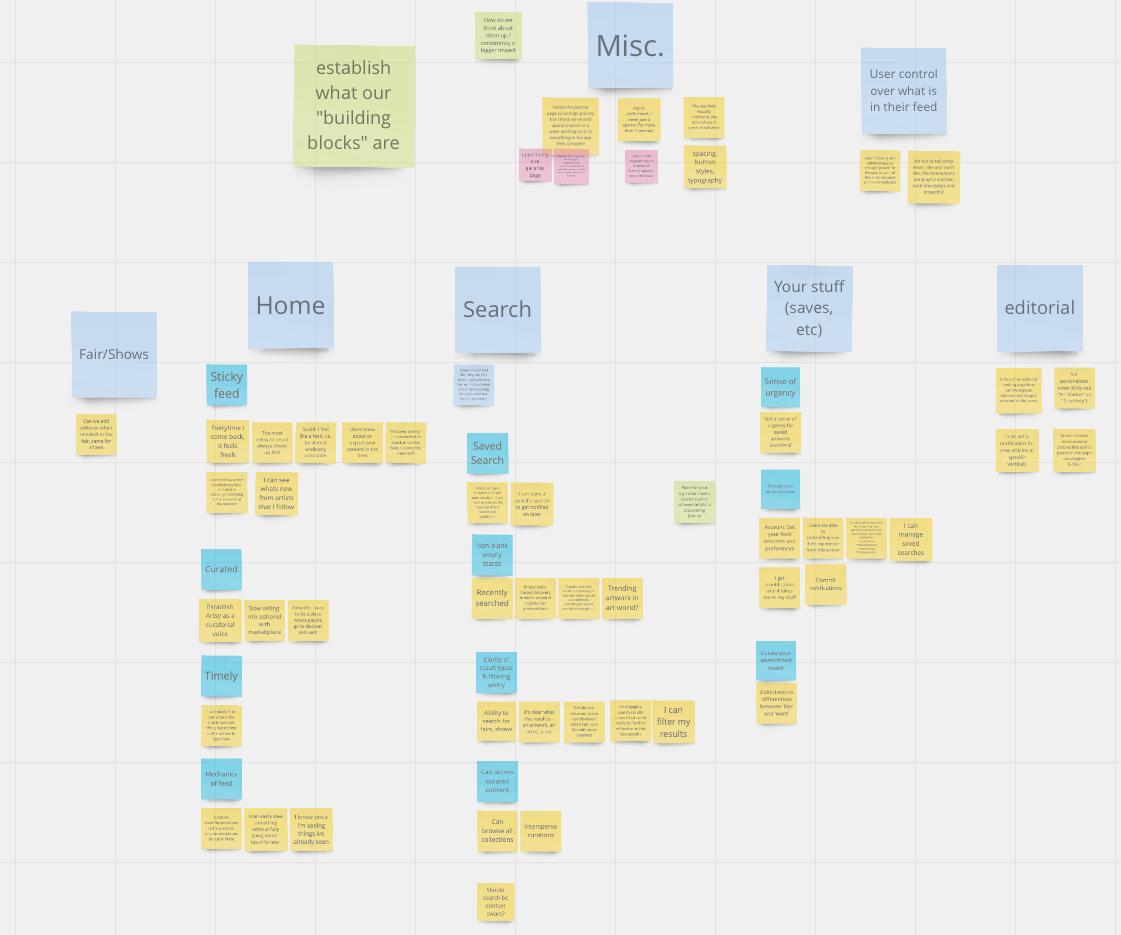

After we decided on our mandate, the next step was to get really familiar with the existing app. We storyboarded out all the existing screens and their connections to one another.

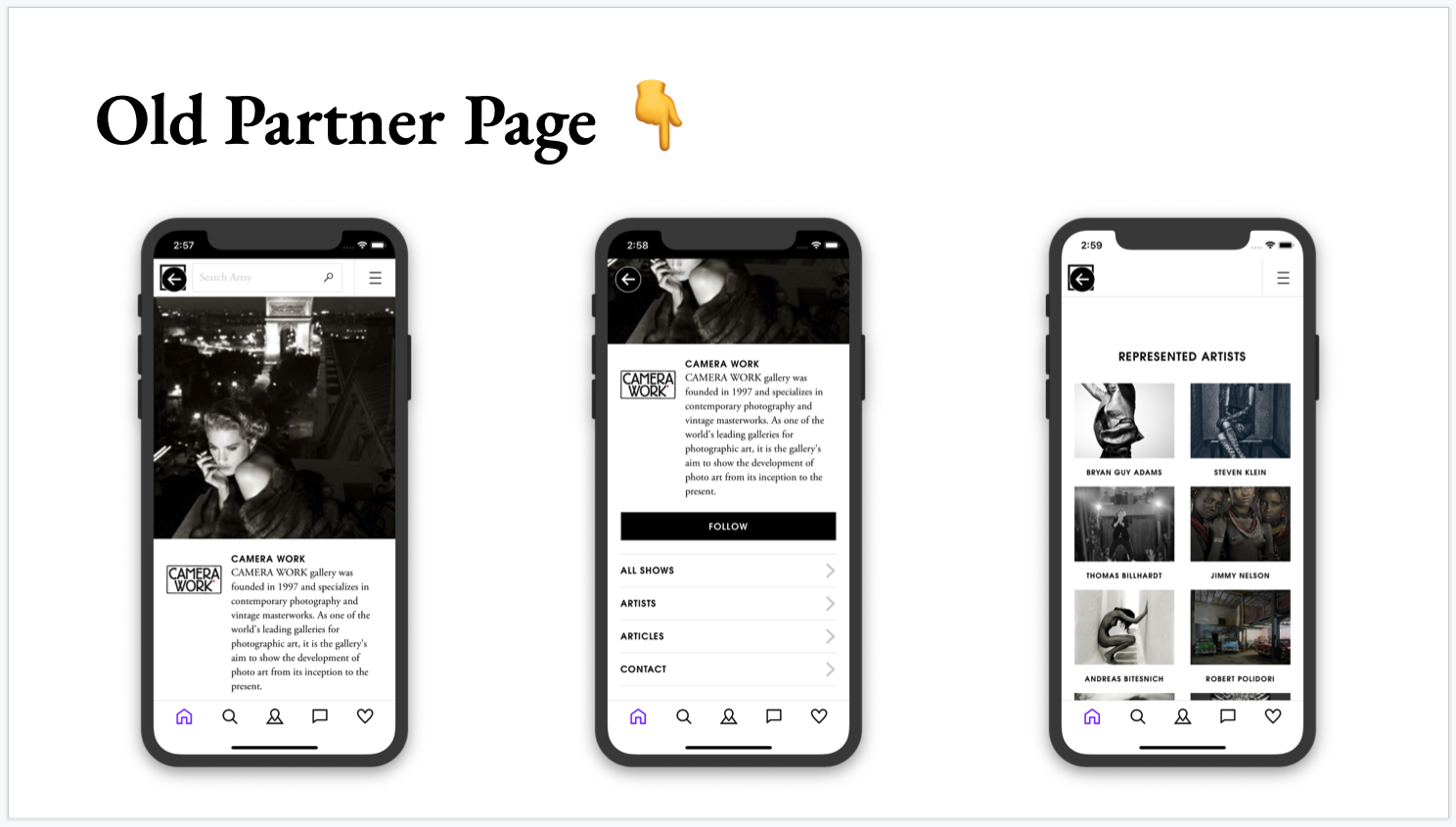

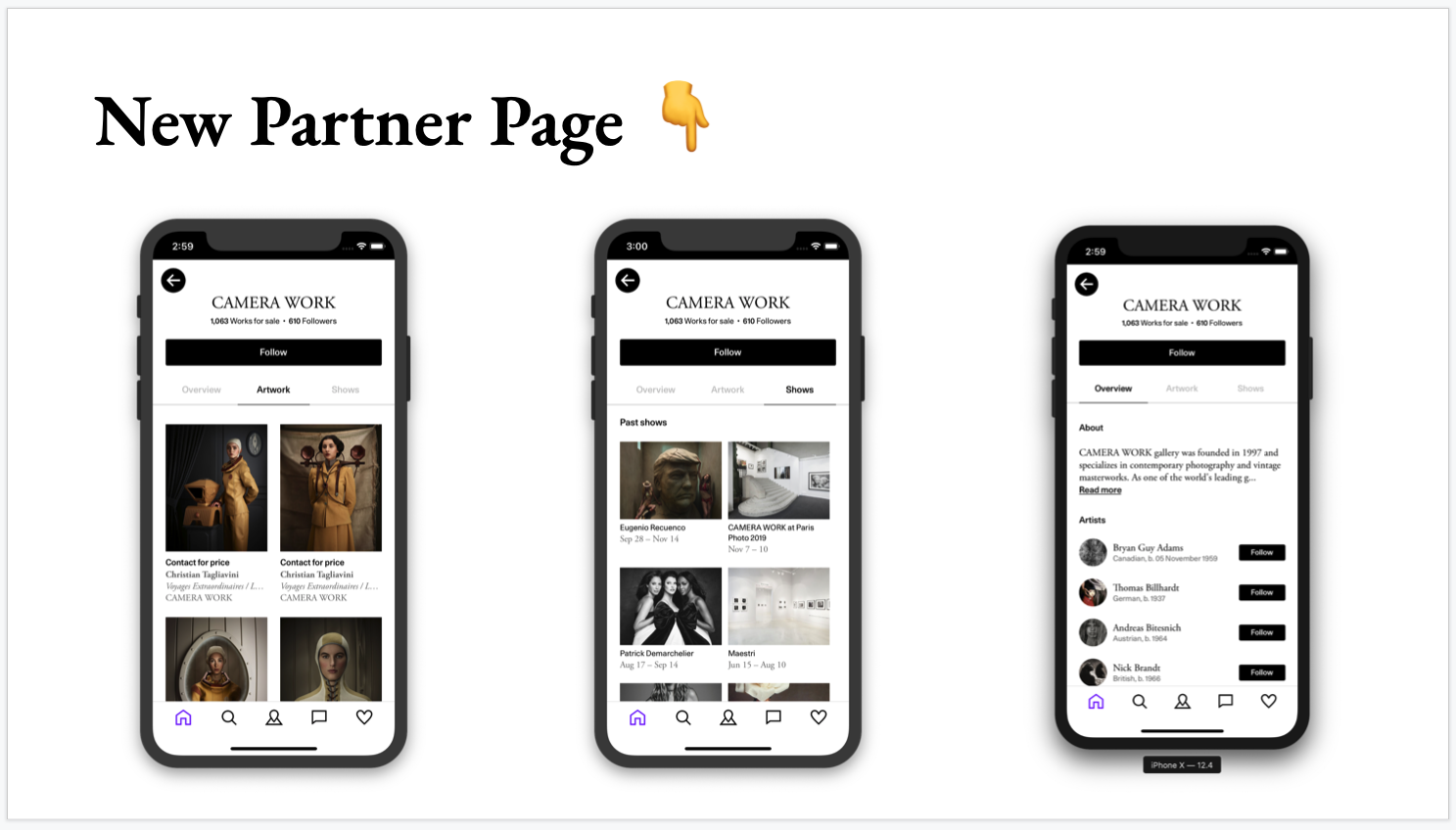

No one on our team had complete knowledge of every screen in the app, not even me, so exploring it together was a great way to uncover what needed immediate attention. One example was our partner page, which displayed information to our users about Artsy’s partners: galleries, museums, auction houses, etc. We learned that the app actually used an ancient web view, and it didn’t even show the partner’s artworks. The artworks! Probably the most important thing for it to do!

This is where “being scrappy” started to take root. Usually when developing new features, Artsy designers iterate on a design before we plan on execution, then we implement, test, and deploy. The nice part of replacing something that was obviously broken was that we didn’t feel beholden to this usual process; whatever we built would be better than what we had. One engineer and our designer started the new partner page with a quick pencil sketch, using the app’s existing UI abstractions to design something that we could quickly build. Once we had a prototype, the engineer and designer iterated. The whole project took only about three weeks.

Early Wins

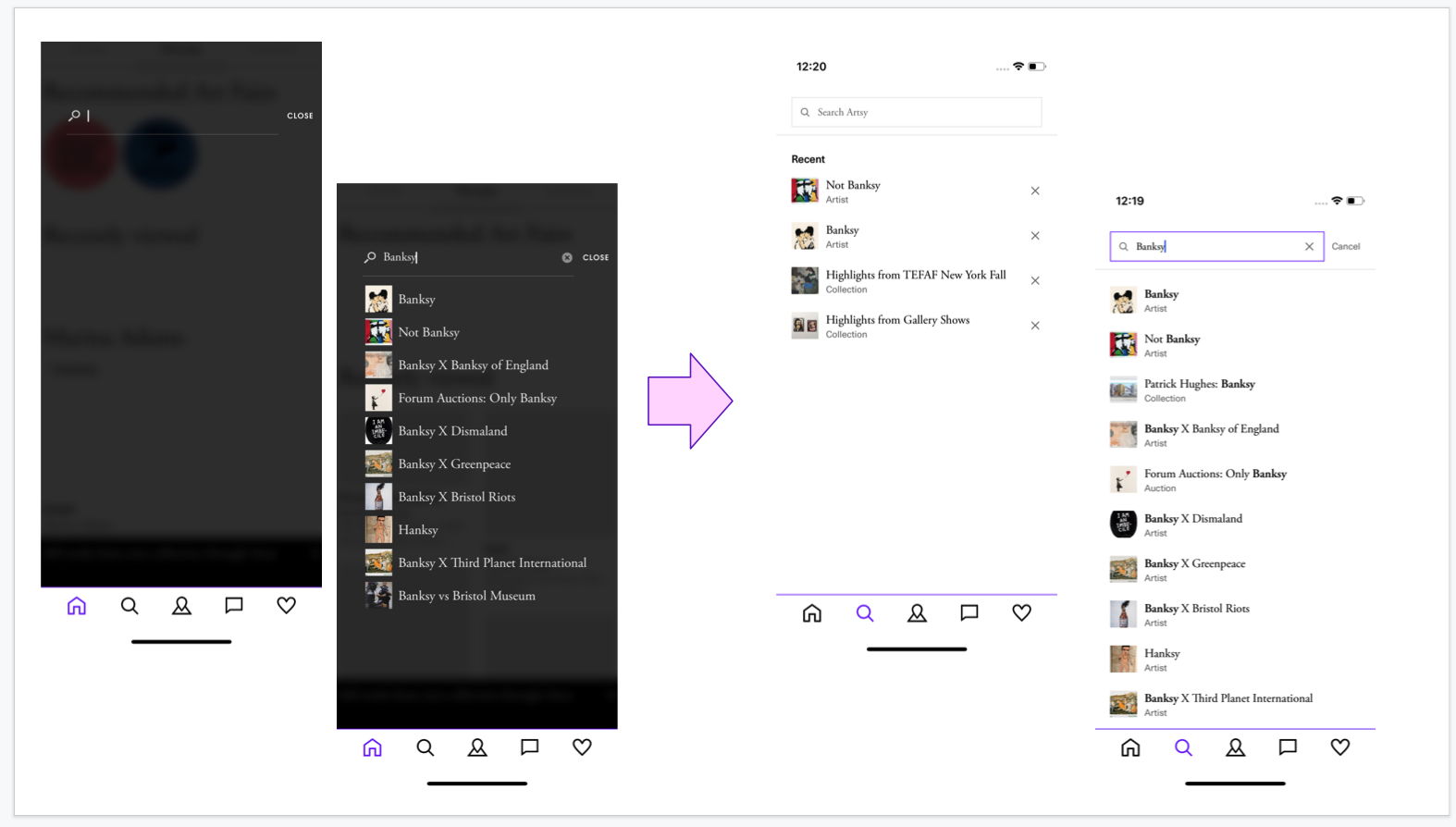

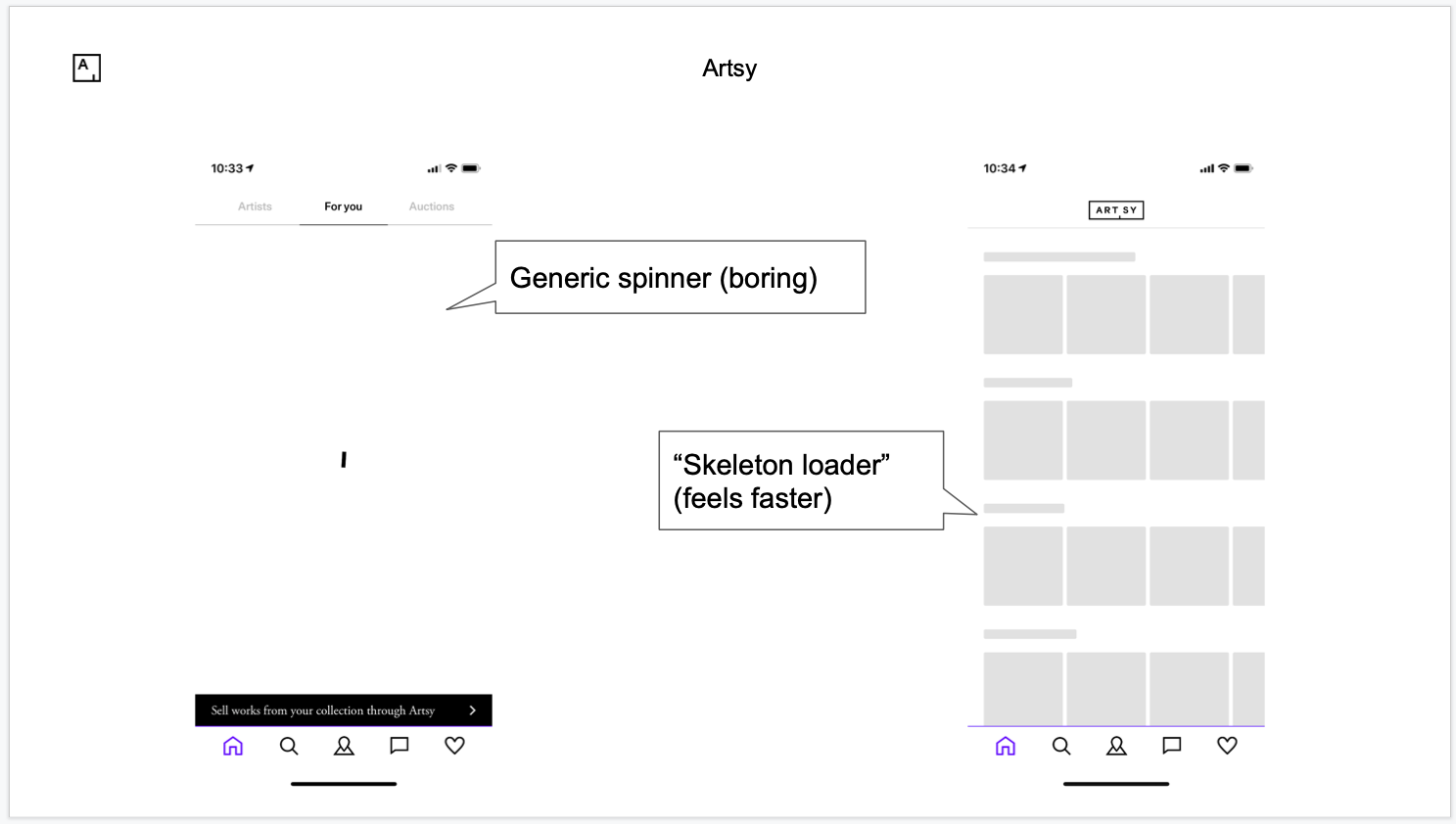

Learning about the app itself was critical, but equally important was learning about how our users used the app. We scheduled user interviews and, in the mean time, looked into our anonymized user analytics. Our data analyst found a few representative sessions and we walked through each action that a user took. One big lesson here was how much our app users relied on the app’s search feature, which was still written in Objective-C and hadn’t been updated in a long time. We found that users would often search for the same query several times in the same session. For example, users would search for “banksy”, wander off exploring some art, and then return to search for “bansky” again. And again. And again.

Our search implementation didn’t show users their own recent searches, which would have greatly reduced the amount of friction users experienced while exploring the art world in the app. Our other engineer took point working with our designer to migrate the app’s search to React Native. We also added some other features to our search page, like adding entity subtitles so users would know if the result they were tapping on was an artwork, and artist, a gallery, and so on. The whole project took about a month to complete, and we have continued to iterate on the app’s search.

In early conversations with company leadership, the Mobile Experience team settled on an… interesting strategy to what we would prioritize. Our mission was “to make the app not suck.” This might seem harsh! But it came from a place of caring. We knew how much better the app could be and we were motivated to make that a reality. In the spring of 2020, the team felt like we had reached a point where the app no longer “sucked” – our goal now was “to make the app amazing.”

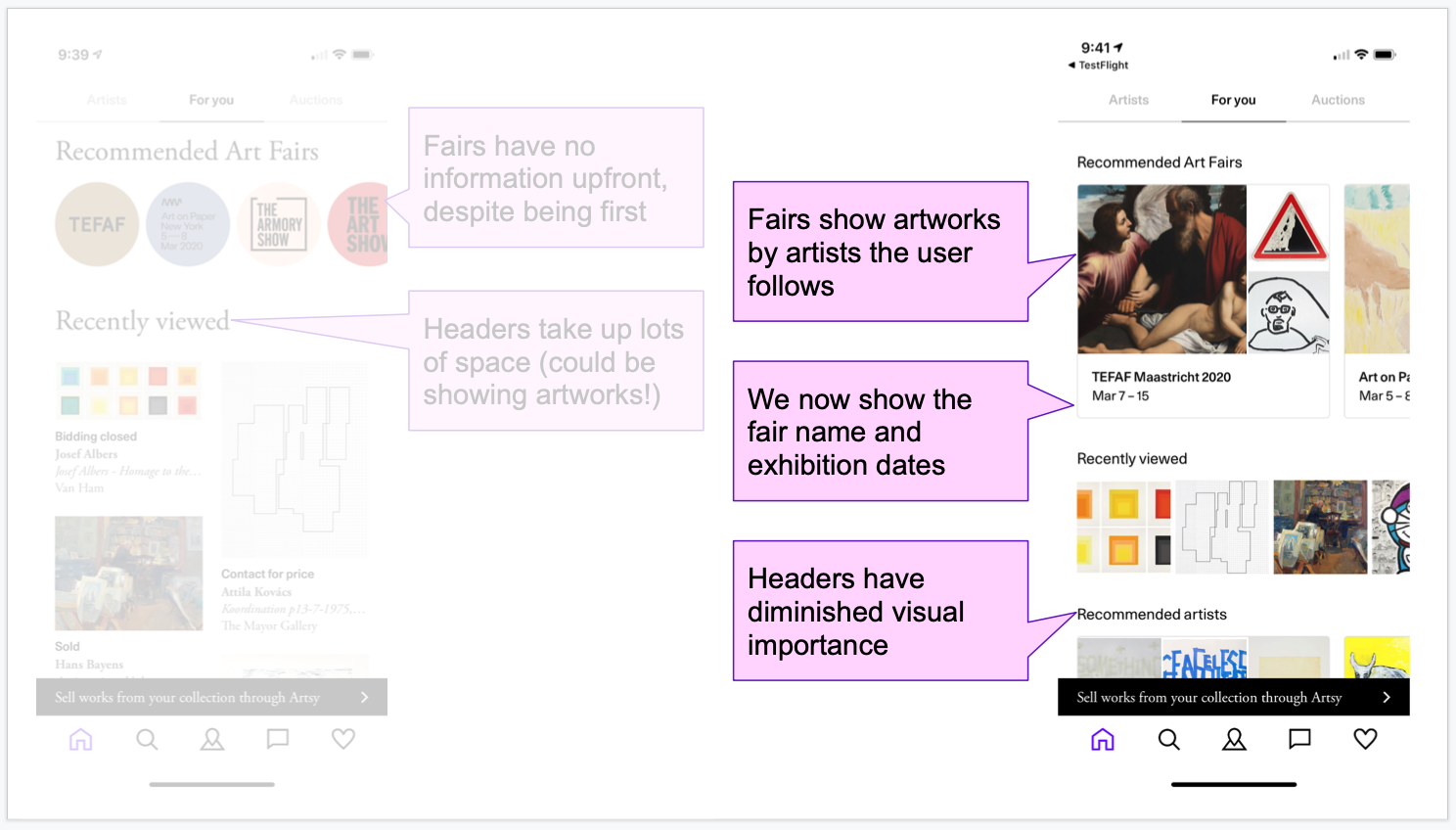

During 2020, we made a lot of changes to the app. We had built a new home page, a profile tab for users, granular push notification settings, Sign In with Apple, and more.

It was really exciting to show off our progress to the rest of the company at our monthly Demo Day, especially in those early months. The product team makes up only a quarter of our company and it was really cool to hear gallery liaisons complementing our new partner page, or sales people complementing our refreshed home feed. I think that people had gotten so used to the app not moving much at all that this sudden high velocity of development was as exciting for them as it was for us.

Setting Up Others To Succeed

Artsy’s goal for the Mobile Experience team was explicitly not to centralize all our iOS feature development, and so our mandate included much more that just working on iOS software ourselves. We wanted to sit between a typical product team and a “platform” team, to provide infrastructure and assistance so any team at Artsy could develop their own iOS feature. This was a big challenge, and required work at the individual and team levels.

The first step was apparent before we even created the Mobile Experience team. Artsy Engineering runs skills surveys every six months, and we knew that building iOS software in React Native was something Artsy engineers weren’t really familiar with, but that they really wanted to learn more about. I worked with the Engineering team’s Peer Learning Working Group to design a curriculum – big shout out to Christina and Adam for their help here!

The iOS Learning Group took four weeks to deliver four lessons. The learners were mostly web engineers, so I emphasized the familiar parts of writing React Native software. I also provided weekly office hours for learners to get assistance with homework. I even stretched my wings as an educator, developing new skills around curriculum design and delivery. After the course, learners responded positively to the experience and we have integrated lessons learned from the iOS Learning Group into subsequent peer learning groups.

Aligning Product Releases

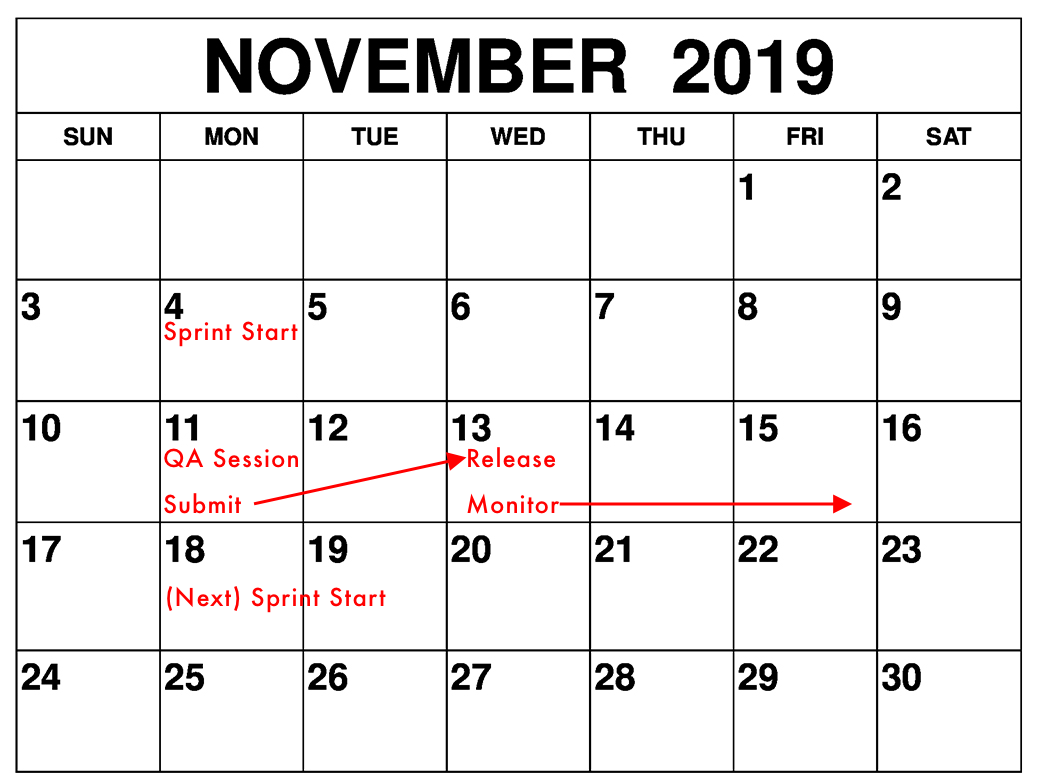

Now that engineers had a solid grasp of how to build software in our application, we could re-align our product development process around iOS. I can’t speak to the design side of this, but from a product perspective the most critical milestone was defining a regular 2-week app release cadence. Let me explain.

Prior to the Mobile Experience team, we released the app pretty irregularly. We would release whenever we had something big to release, basically. There are two major flaws with that approach. The first problem is that since each release was bigger, each release was scarier. No one really felt confident releasing app updates. The second problem was that large pieces of work tended to get coupled together. This came to a head last summer when we were blocked from releasing an redesigned artwork view because we were waiting for a major overhaul to Artsy’s GraphQL API to be completed. Without guidance or structure, different teams were building big projects and both had their changes in our default branch – it was a bit chaotic.

These two problems are incidental to how we worked at Artsy but there is another, inherent problem to developing mobile apps: deploying iOS software is weird. Engineers, designers, and product managers at Artsy are used to being able to quickly and cheaply deploy software to the web, not the App Store. iOS software is deployed to our user’s hardware, not to servers we control, which introduces the possibility that users might not upgrade. Software we shipped years ago is still being run today – we have the analytics to prove it. Not to mention that every app update has to go through Apple’s App Store review process. Getting our product team aligned on a release schedule might also help us get aligned on the weirdness of deploying iOS software.

iOS developers! I have a question for you. I hear a lot about teams releasing app updates on a 2-week cadence, to increase user confidence/App Store ranking/team morale/etc.

— Ash Furrow (@ashfurrow) October 17, 2019

Have any teams shared their experiences with this? Bonus points for any quantitative data. Thanks!! 🤗

As the Mobile Experience team formed, I reached out to other mobile teams to find out about how they structured regular releases. Matt Greenwell from BuzzFeed was really helpful in particular, outlining their experience of the pros and cons of a regular release cadence. We implemented a two-week release cadence so that all product teams could align their own feature development and testing around this predictable structure. We also created documentation for teams to hide their in-progress work behind feature flags. And finally, we refined our app QA process; teams would QA their own features and bug fixes while the Mobile Experience team would used a QA script to test the app generally, every other Monday, before submitting an update to the App Store.

Making Deploys Not Scary

To further help teams get into the habit of developing and releasing iOS software often, we created nightly betas. We also adopted a clever idea from our web colleagues: deploy blocks. In case of a technical reason to not release a beta, we create a block and the CI job that deploys the beta would fail with a descriptive message. This reduced a lot of chatter in Slack where engineers would ask “could I make a new beta?” Instead, engineers usually just wait for the nightly beta. And if they get impatient, they now default to action (their beta deploy will fail if we set up a block).

All of this was automated through fastlane on our CI provider. We had been using fastlane

for a long time at Artsy, but the Mobile Experience team took the time to share knowledge of how it worked. Any

engineer at Artsy can now make a beta (make deploy) or promote the latest beta to an App Store submission

(make promote_beta_to_submission).

We deploy more often and, consequently, each deploy is less scary. And everyone is aware of the need to hide in-progress work behind feature flags. At this point, updates to our app are mundane, predictable, and boring. Just the way we like them.

Being Generous With Our Time

Our QA and deploy process touches on something I want to go into more detail about, which is how the Mobile Experience team helped support other product teams. I described earlier how Mobile Experience sits somewhere between a normal product team and a platform team, and we leveraged that to our advantage. It would have been easy to become primarily a supportive team, and leave feature development up to others. However, that would leave us unaware of how day-to-day development feels in the app. We own the platform, and that includes the developer experience. By sitting in this ambiguous in-between state, we stayed aware of both the needs of everyday developers, and the needs of our platform.

I would encourage engineers from other teams to ask us for help, which led to a lot of pairing sessions. To be honest, I think it probably interfered with our productivity, but it was worth it. A half hour of my time spent pairing with a colleague might save them three hours of banging their head against Xcode. But it’s not the time saved that I care about, it’s the head-banging. I want engineers at Artsy to feel empowered to build their own iOS software, and that’s only going to happen if they feel comfortable and supported.

When the Galleries team kicked off their ambitious Viewing Rooms project, we helped them get started by lending an engineer to them for a few sprints. When they ran into problems, we were generous with our time by pairing with them. When they were nearing completion, we helped them test the new feature. This all culminated in a smooth release.

Speaking of Developer Experience, we took a keen interest in standardizing our best practices and modernizing the codebase. We documented how we wanted the app’s codebase to look and set up processes like lint rules to encourage developers to follow our best practices. We also invited any engineer at Artsy to join our twice-weekly Knowledge Share meetings (I’ll discuss these in-depth shortly). We looked for bottle necks in the development process and found many problems, which we addressed. We combined the Native iOS and React Native repositories (which had historically been separated). We overhauled the CI configuration to leverage heavy caching – average build times dropped from fifteen minutes to less than five. And we adopted stricter TypeScript compiler settings so that engineers would be forced to deal with nullability and other causes of bugs. (Hey, sometimes you need a carrot and sometimes you need a stick.)

The React Native community has grown a lot since 2016. If Artsy were to begin our adoption of React Native today,

we would be really well-supported by a community that has defined best practices, documented standard approaches to

problems, and a consolidated opinion on what a React Native codebase should “feel” like. None of that existed in

2016, and our early architectural decisions don’t really reflect contemporary best practices. We continue working

to bring our codebase closer to resembling a fresh project created with react-native init.

I’m extraordinarily happy with how things have shaped up, and in the direction we continue to move. This is all an ongoing process, and should remain an ongoing process. For example, engineers were still facing a bottleneck with core parts of our app’s routing logic that were in Objective-C, so we recently moved all routing to TypeScript. Not only does moving code out of Objective-C make it easier for everyone to build, but it also ladders up to a cross-platform Artsy app.

We still have older practices in the app that we want to migrate away from, like testing with Enzyme. But overall, things are looking good!

Knowledge Shares

We achieved most of these big, infrastructural changes in meetings called Knowledge Shares, which I mentioned earlier. I should write a dedicated blog post on these (update: I did write one), but in short: Knowledge Shares are a structured time to facilitate unstructured learning. Anyone can bring a topic to Knowledge Share, from a ticket that they’re stuck on to an idea they have to a neat trick they recently learned. We set aside these two hours a week to discuss whatever the team wants, and we don’t only invite engineers.

New feature designs, product roadmaps, and data analyses are often brought up by our non-engineering colleagues; we discuss these at the beginning of the meetings to make sure everyone’s time is respected. Throughout the week, someone will raise a question in Slack. Before we had Knowledge Share meetings, we might schedule a dedicated half-hour meeting to discussing this question. But instead, we now say “alright let’s chat about this at tomorrow’s KS.” Usually the discussion lasts a lot less than a half hour, so we save time and needless context-switching.

Knowledge Shares are also a manifestation of my philosophy of tech leadership, which is this: none of us have built an Artsy before, so instead of optimizing for building an Artsy, let’s optimize for learning how to build an Artsy. The best Artsy we can build. And as a natural byproduct, an Artsy gets built. But it’s the learning that is treated as the paramount goal.

Like I said, I owe you a whole blog post on Knowledge Share meetings. I hope I have conveyed how important these scheduled “structured unstructured learning” times have been for us.

The Results

So where does that leave us? It’s been a year and change, where are we now? Well I’m happy to say that we’ve made a huge impact. We’ve gone from only having (at most) one product team writing iOS software at a time to having nearly every product team building iOS software. Artsy is through the woods of its transition to a mobile-first product strategy. We still have a ways to go, but it feels like we have finally realized the dream we had in 2016 where every team is fully equipped and empowered to deliver on their own business goals, across all of Artsy’s canvasses.

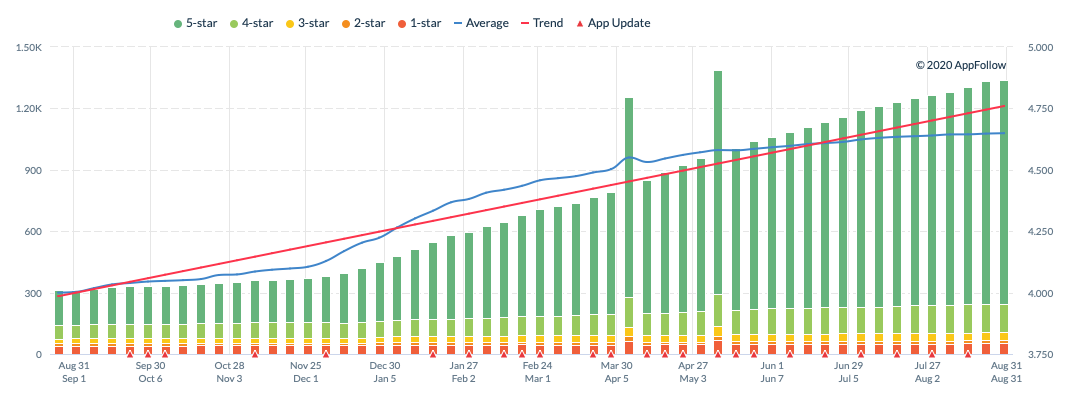

Our App Store ranking has shot through the roof – not surprising considering our “make it not suck” and then “make it amazing” approach. Artsy’s iOS app rating now sits at a stout 4.7.

We’ve also started tracking our iOS developer experience within Artsy. We know exactly where we still need work because we ask our engineers where they need support.

It’s taken a mammoth effort, and there’s so much more that I could talk about, but this blog post is long enough already! Looking at the work we’ve done, the ways we’ve done it, and the results of our effort… I feel ecstatic.

Next Steps

All that said, Artsy’s product team is currently embarking on another reorganization. With so much technical and product debt paid off, Artsy has evolved past the need for a dedicated Mobile Experience team. It’s bittersweet, but I’m proud to say that the new Collector Experience team is about to be born. Our team will continue to own the mobile platform, including its holistic user experience and day-to-day developer experience, but we’ll have an expanded mandate. That mandate includes a cross-platform Artsy app that will work for collectors on Android as well as iOS.

The Mobile Experience team has grown, too. Since we started last year with just a few engineers and limited product support, we now boast a full roster of engineers and product support. I want to thank everyone on the team, currently: David, Sam, Brian, Mike, Brittney, Pavlos, and Mounir. You have made the past year an incredibly rewarding experience for me as I learn the ropes of technical leadership. I’m so proud of what we’ve built together and I’m excited for what the new Collector Experience team is going to do next!