React Native is a new native library that vastly changes the way in which you can create applications. The majority of the information and tutorials on the subject come from the angle of “you are a web developer, and want to do native”.

This makes sense, given that the size of the JavaScript/web audience is much bigger than native developers, and far more open in the idea of writing apps using JavaScript. For web developers it opens a new creative space to work, however for native developers it provides a way to work with different tools on the same problem. Considering that most developers with a few years on the platform will be comfortable with the Xcode suites of tools, recommending a change this drastic is a tough sell.

We’ve been using React Native now for about a year and a half, and have started to slow down on sweeping changes inside the codebase. This is great because it means we’re spending less time trying to get things to work, and more time building on top of a solid foundations. Now that we’re settled, it’s time to start deeply understanding what happens with React Native.

I’d like cover a lot of the common questions we get asked about from the perspective of native developers:

- What is React Native?

- How do you use React Native?

- When is React Native a good technology choice?

This article covers an awful lot, so free up at least 45 minutes, make a tea and then come back to this on your computer. It’s worth your time if you’re interested in all the hype around React Native.

Before you get started, it looks like you're using a really small screen, this post is built for larger screens and having a terminal around will make it much easier to understand the ideas inside the post. So if you can, please switch to a different device. You will be missing sections otherwise.

At the highest level, React Native is a way to write React apps that run as native programs. You write your app’s code in JavaScript, and React Native bridges that code with native UIView elements. React Native has two stated aims:

- Learn Once, Write Anywhere.

- Make a native developer experience as fast as the web developer’s.

“Learn Once, Write Anywhere” is a play on Java’s “Write Once, Run Anywhere” - something that has not worked well for user-interface heavy mobile clients. The idea of running the same code everywhere encourages platform-less APIs which water down the positives of each platform.

“Learn once” in this context means that you can re-use the same ideas and tools across many platforms. You don’t lose your ability to write the same user experiences as you can with native code, but you can re-use your existing skills across different platforms. That is the “Write Anywhere” aspect.

React Native makes it feasible to share a lot of code between iOS, Android and Web. It is not a panacea for making a cross-platform app though; cross-platform is not an explicit goal of the project. The project moves towards making the best per-platform apps.

To make a developer experience as fast as the web developer’s you need to really reflect on how slow native development is. A change in one part of the app required a full restart of the simulator, and for the developer to get back into the same position to see the changes. As a web developer you would just refresh the browser. For example with the simplest Xcode iOS app template, I made a single line change and did an incremental rebuild and it took 9 seconds to get me back into my app with the new change, on a 2015 MacBook Pro. 9 seconds per change leaves a lot of time to lose focus, and discourages playfulness.

If those are the stated goals of React Native specifically, what are the goals of React?

React

React provides a single-direction Component model that can handle what is traditionally handled by the MVC paradigm. The library was created originally for the web, where updates at the equivalent of UIView level are considered slow. React provides a diffing engine for a tree of components that would eventually be represented as HTML, allowing you to write the end-state of your interface and React would apply the difference to only the HTML that changes.

React was built out of a desire to abstract away a web page’s true view hierarchy (called the DOM) so that they could make changes to all of their views and then React would handle finding the differences between view states.

This pattern is applied by providing a consistent way to represent a component’s state. Imagine if every UIView subclass had a “setState” function where you can send a subset of all available options (backgroundColor, frame, alpha, etc) and then eventually UIKit would reconcile all changes to all views in batches.

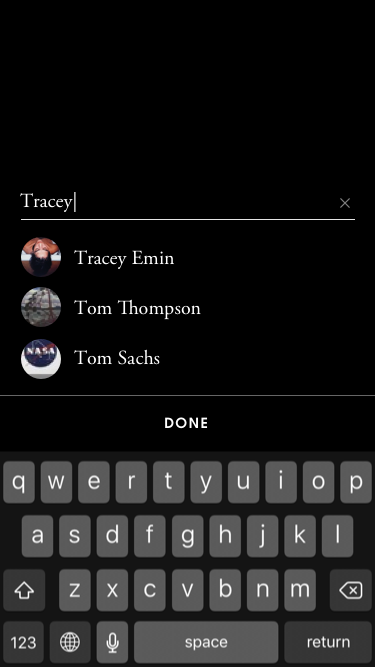

To get a sense of what this feels like, I’ve created a simplified version of the React components for one of the screens in our app, the full implementation is here. You can see the original design, a prototype of how that is then split into components, then the tree structure for those components and finally the props for each component.

View

SearchQueryInput

ScrollView

ArtistResult

ArtistResult

ArtistResult

Button

// Hover on prototype for props

{

...

}

This kind of tree structure should feel quite similar to the UIView tree that you see inside a tool like Reveal, or inside the Xcode visual inspector. Next up I want to show you what the code for this would look like in JavaScript:

// Import React, and native components from React Native

import * as React from "react"

import { ScrollView, Text, Image, View } from "react-native"

// Re-use our existing search TextInput component

import TextInput from "./text_input"

// Exports a React component called Search Results from this file

export default class SearchResults extends React.Component {

// The tree of components that this component represents

render() {

// This is JSX code, JSX is a source-code transformer that converts code from

// HTML-like brackets into a specific method call. E.g `<Text font="Garamond" />`

// turns into; `React.createElement('Text', {font: 'Garamond'}, null)`

return (

<View>

<SearchQueryInput text={{ value: props.query }} onChange={this.onQueryChange.bind(this)}/>

<ScrollView>

{props.results.map(rowForResult)}

</ScrollView>

</View>

)

}

// Returns a single component for a row in the search

rowForResult(result) {

return (

<ArtistResult>

<Image source={{ uri: result.url }} />

<Text>{result.name}</Text>

</ArtistResult>

)

}

// A function to handle changes to the search query

onQueryChange(query) {

...

}

}

You’re looking at a subclass of

React.Componentwith two functions,renderandrowForResult.renderis the key function for defining your tree.

Instead of MVC, React uses composition of components to handle complexity - this should feel quite similar to iOS development. The screen of an iOS app is typically made up of UIViews, and UIViewControllers which exist as 2 interlinked trees of hierarchy. A UIViewController itself doesn’t have a visual representation, but exists to manipulate data, handle actions and the view structure for UIViews who do.

By merging the responsibilities of a UIView and UIViewController into a Component, there is a consistent way to work with all aspects of your app.

To try to understand this, let’s take a trivial example. Downloading some data from the network and showing it on a screen.

In UIKit-world you would:

- Create a

UIViewControllersubclass, which makes the API request on itsviewDidLoad - While the request is sent you present a set of views during loading

- When the API request has returned, you convert the data into native model objects, remove the loading screen

- You then create a new view hierarchy for your model, and pass down attributes of the model to those views

In React you would:

- Create a

React.Componentsubclass, which makes the API request on itsonMount - While the request is sent you render a set of components during loading

- When the API request has returned, you change your “state” on the main component with the API request’s JSON

- The state change re-runs your render method, which passes the API “state” down to the component for your page

They are conceptually very similar. React does two key things differently: Handle “state” changes on any component, and handle view creation/addition and removal.

Handling “State” Changes

So, I’ve been quoting “state”, I should explain this. There are two types of “state” inside React, and I’ve been using the quoted term to refer to both for simplicity till now.

There are two types of data that control a component:

propsandstate.propsare set by the parent and they are fixed throughout the lifetime of a component. For data that is going to change, we have to usestate.

So in our case above, getting the API results only changes the state on the component which makes the request. However, the results are passed down into the props (properties) of the component’s children as any further changes to the API data (for example if you were polling for updates) would result in a re-render of the child-components.

So for the lifetime of that top-level component, the changes due to the API request are put in state. Then the results are passed down to its children as props. This means the children can potentially change when an API response is received.

This is a hard abstraction to grok outright, so it’s good to take a second opinion. I felt that this guide from uberVU as well as the official docs above explain it in different ways. Which can help ground your understanding. Overall, these are the rules:

props state Can get initial value from parent Component? Yes Yes Can be changed by parent Component? Yes No Can set default values inside Component? Yes Yes Can change inside Component? No Yes Can set initial value for child Components? Yes Yes Can change in child Components? Yes No From uberVU’s react-guide

Handling View Management

Because of the consolidated rules around state management React can quite easily know when there have been changes throughout your component tree and to call render for those components. render is the function where you declare the tree of children for a component.

The flow [of data] in React is one-directional. We maintain a hierarchy of components, in which each component depends only on its parent and its own internal state. We do this with properties: data is passed from a parent to its children in a top-down manner. If an ancestor component relies on the state of its descendant, one should pass down a callback to be used by the descendant to update the ancestor.

React Native - Communication between native and React Native

Props are treated as the equivalent of a Swift let variable in this case, any changes to props require a new version of the component to exist in the tree and thus render is called.

So, in summary: React’s paradigm is a component tree, where the render function of a component passes down one component’s state into the props of the children.

React Native

React was built for the web - but some-one realised that they could de-couple the React component tree from the HTML output, and instead that could be a tree of UIView’s.

That is the core idea of React Native. Bridge the React component tree to native primitives. React Native runs on a lot of platforms:

- Officially: iOS, Android, tvOS & VR.

- Unofficially: macOS, Windows & Ubuntu.

Each of these platforms will have their own way of showing some text e.g.

RCTTextfor iOS and tvOS - which uses NSTextStorage, and drawRectTextfieldfor Android - which uses Canvas and a DrawCommandThree.js view primitivefor VR - which uses BitmapFontGeometry + ShadersRCTTextfor macOS which also uses NSTextStorage, and drawRectReactTextShadowNodefor Windows - which uses a RichTextBlockQQuickItemfor Ubuntu - Which uses QString to render

But when working at React-level, you would use the component Text. This means you work at a “React in JS” level, and rely on the primitives provided by each implementation of React Native.

For iOS, this works by using a JavaScript runtime (running via JavaScriptCore in your app) which sends messages across a bridge that handles the native UIView hierarchy. Most of the messaging work is handled inside the RCTUIManager which receives calls like createView:viewName:rootTag:props:, setChildren:reactTags:, updateView:viewName:props: and createAnimatedNode:config.

This bridging is how you get a lot of the positive aspects of working with the JavaScript tooling ecosystem. The JavaScript used by React can be updated independent of the app, but so long as it is working with the same native bridge version. This bridging technique is how React can safely have a reliable version of Injection for Xcode. It re-evaluates your JavaScript code, and that triggers a new set of messages to the native side.

Like any cross-platform abstraction, React Native can be leaky. To write a cross-platform app that purely lives inside JS Runtime, you have to write React-only code. React and React Native doesn’t have ways to handle primitives like UINavigationController - they want your entire app to be represented as a series of components that can be mapped across many platforms.

This isn’t optimal when you’re coming in from the native world - where you’re used to building platform-specific experiences, and are genuinely excited at the prospect of platform-specific APIs. Generally you can look for other teams who have felt the same and are willing to write native-bridged code that’s specific to iOS. Shout-out to Wix and AirBnB who are doing great work in this space.

Is this a critical problem against React Native? I don’t think so, we’ve added native abstractions where it was the right decision and we’ve used JavaScript when it was the right decision.

For example, our Image component is a bridged native component that uses SDWebImage under the hood so that we can share an image cache for thumbnails with the native side of the app. It works by:

- Declaring a JavaScript component to represent your native component

- Letting React Native know you mean to reference native code for your component

- Creating a native view with the same interface as your props

- Using bridging macros to expose your interface to JavaScript

Here is a commit that initially added the native component, before it became more complex from production usage. The bridging macros cannot be used in Swift, but you can still bridge to existing Swift code too.

This fundamentally means you can have both: a faster more elegant way to write your interfaces and the ability to still work with any part of the native toolchains you want. You can pick based on the problem, and the domain.

Ten minutes to try out React

OK, no joke, don’t skip this bit, you try React Native right now. This will require some terminal skills, and about 5 minutes, it shouldn’t be more complex than using CocoaPods via the terminal.

# If you don't have homebrew

# see https://brew.sh

# Install the JavaScript tools you'll need

brew install nodejs yarn

# You'll want Visual Studio Code to work on this

brew cask install visual-studio-code

# Install the React Native CLI

yarn global add react-native-cli

# Create a new React Native

# project called TrendingArtists

react-native init TrendingArtists

You'll need node and yarn installed globally so you can run JavaScript and handle dependency management respectively.

For working inside a JavaScript project, I'd strongly recommend using Microsoft's Visual Studio Code, it does a great job for React Native.

Next up we're going to make the initial project and look around, so once all the installing has finished. You can follow along with the next section.

If the command `react-native` isn't working, @keitaito has some useful advice in the comments.

Alright, so that should do a lot of downloading, and you’ll have a new folder with a fully set up project for iOS and Android. We’ll be focusing on the iOS side.

Open up TrendingArtists in your editor and inside your terminal with cd TrendingArtists then code .. From the terminal you can get the Xcode project compiled, and your new app open inside the iOS simulator with react-native run-ios. This will will set you up to work without Xcode.

The run-ios command first uses xcodebuild to compile the native app found in ios/TrendingArtists.xcodeproj it will then load up the the React Native Packager. We’ll cover that later, for now, think of it as a JavaScript file change watcher.

Once a simulator has popped up, you’ll see the “Welcome to React Native” screen. Now that we’ve got “an app” running. It will take a minute or two to parse all your JavaScript. So then let’s take a moment to look through what we have in our file system now.

# If you want tree: brew install tree

$ tree .

├── __tests__

│ ├── index.android.js

│ └── index.ios.js

├── android - [snipped]

├── app.json

├── index.android.js

├── index.ios.js

├── ios

│ ├── TrendingArtists

│ │ ├── AppDelegate.h

│ │ ├── AppDelegate.m

│ │ ├── Base.lproj

│ │ │ └── LaunchScreen.xib

│ │ ├── Images.xcassets

│ │ │ └── AppIcon.appiconset

│ │ │ └── Contents.json

│ │ ├── Info.plist

│ │ └── main.m

│ ├── TrendingArtists-tvOS

│ │ └── Info.plist

│ ├── TrendingArtists-tvOSTests

│ │ └── Info.plist

│ ├── TrendingArtists.xcodeproj

│ │ ├── project.pbxproj

│ │ ├── project.xcworkspace

│ │ │ ├── contents.xcworkspacedata

│ └── TrendingArtistsTests

│ ├── Info.plist

│ └── TrendingArtistsTests.m

├── jsconfig.json

├── package.json

├── node_modules [x million files snipped]

└── yarn.lock

What are we looking at?

First up - we have some test files, these files are unique per platform - though they do have the same code right now. In React Native imports can resolve to be different per-platform, which is why you see .android.js or .ios.js.

index.android.js and index.ios.js are the launching point for this app, so it's in there you'll find the code for what we're seeing on screen.

In the ios folder, we have the native side of React Native. Looks pretty empty from here, but when you open the workspace you'll note that it is referring to a lot of xcprojects which are inside your node_modules folder.

The Xcode project is really barebones, it's just an AppDelegate that creates a UIView subclass. You can see that it references index.ios.js which is where your JavaScript side starts.

Then you have the package.json which is like an Xcodeproj + Podfile in one, and the node_modules folder. This file houses all your JavaScript dependencies, your runtime scripts and app metadata.

I’d like to show you how to make a change appear instantly. In your iOS Simulator, perform a shake gesture (cmd + ctrl + z) and in the React Native debug menu, hit “Enable Hot Reloading”. It will trigger a reload of all your JS code again.

Now you can go into your text editor and change some of the words inside index.ios.js - those changes will be reflected almost instantly. You can do this for almost anything, almost anywhere. We’ve been working on Emission for over a year, and this is still close to instant in every part of the codebase.

One of the key changes here is that React Native will occasionally make you wait a bit longer (parsing all of the JavaScript) in exchange for very often giving you sub-second changes reflected on screen. This is an incredibly positive change from 9 seconds per iteration from my blank native app.

This substantially changes how easily I can focus on my work in React Native, and how effortlessly I can experiment with code. It makes me feel really productive, and makes pairing a joy.

If you’d like to go through a tutorial from this point, I’d recommend these:

We’re now going back to talking about the hows and whys. Good luck with those tutorials though - you’ve got this :D

Writing JavaScript

JavaScript is a deceptively simple language with a lot of weird gotchas, which makes it easy downplay. Especially coming from the native world, where you are used to vendor-owned programming languages which are more focused and have useful type systems.

I think it’s safe to say that the majority of JavaScript’s warts are fixed by community tooling nowadays. Tools like ESLint, TSLint, Babel, Prettier, TypeScript and Flow make it difficult to write bad code, and the JavaScript community really comes together to fix it’s own problems. This differs from the Sword of Damocles that exists for big OSS projects in the iOS community.

Here’s a collection of tools that we use every day in the JS world:

| Project | What it does | Why it’s awesome |

|---|---|---|

| Babel | Transform source code | You can pick and choose language features |

| TypeScript | Transform source code | Microsoft choose all your language features |

| NPM | CocoaPods for JS | Make your own standard library |

| Yarn | Improved CocoaPods for JS | An NPM compatible re-think of the NPM CLI |

| ESLint | Static code linter | Makes it hard to write bad code in JS |

| TSLint | Static code linter | Makes it hard to write bad code in TS |

| prettier | Code formatter | Never argue about syntax for JS/TS/CSS/JSON |

| Jest | Test runner | Fast, watches for changes, runs only changed code, etc |

| Storybooks | Prototyping environment | Make browsable scenes of state + components |

| Husky | Simplify Git Hooks | Easily ensure code is consistent |

| DangerJS | Code review automation | Stop asking for CHANGELOG entries etc |

| Metro Bundler | Code bundler for React Native | Handles code changes at runtime for you |

These inter-linked, composable tools basically represent the entire idea of the JavaScript community. You add them to your project, and your project gets all these small config files that eventually create the kind of cohesive tooling that you would expect from a single vendor in a native environment.

The good part is that they are interchangeable, for example, we switched from Flow to TypeScript with roughly 2 weeks work, then a week to come close to perfect. The bad side is that the configuration aspects of these projects feels like something you do once, then forget until it needs to change.

I wrote up a glossary of terms from JavaScript when I first started understanding the community, you can find it here.

“But JavaScript is such a downgrade compared to Swift”, I hear you echoing from the back. This is my own perspective but I consider my workflow in TypeScript to be significantly better than working in Swift. My code is statically analyzed as I type, it is auto-styled as I save, my tests are instant, permanently running and show inside my editor at all times, it’s portable across platforms, it’s quick to execute and embarrassingly fast to compile. I can contribute to all of these tools to improve them. I’d rather work in that environment.

Syntax wise, TypeScript doesn’t have enums with associated types, which I like, nor implicit trailing closures. As a trade-off though TypeScript has union types, which work really well for data-modeling.

One particular thing I like a lot about JavaScript that the code you read is generally simpler, as nearly all symbols that you use need to be defined in that file. This is because you can only import a single file, instead of an entire target. Meaning if you include a library, you either import the functions you want, or the library as a whole and then extract the functions, and variables that you want.

If there’s one major flaw with the JavaScript code we have written so far, it’s the complicated ugliness surrounding the this keyword. It is genuinely complicated, and a good source of dev-time errors for me. No linters can really catch those errors, so it becomes frustrating.

Node.js

Next to React Native, there are two main environments for writing JavaScript in: the browser, and inside Node. Node is the JavaScript runtime from Google Chrome (called V8, their version of JavaScriptCore) with a UNIX-like baseline set of APIs.

It provides relatively few APIs, it is expected that you would use an NPM module for anything particularly high level. The principle being that a standard library (like Foundation in iOS) is always going to be out of date, and incompatible with what web-browsers ship.

An NPM module is a set of JavaScript files with a particular structure. Generally, there is a package.json to describe the library, and an index.js with the code for the library. Libraries can be as small as a single-function to a typical “XYZKit” you would expect from a CocoaPod. As JavaScript tends to be bundled and minified based on code used, developers mainly worry about the overall file-size of their library. You would use a package manager like NPM or Yarn to manage these dependencies. Node modules have the unique, and dangerous idea of allowing multiple versions of the same library to exist inside your application. This “fixes” the problem of dependency hell, at the cost of potential runtime issues. Here’s a full explanation of the pattern.

When writing JavaScript with React Native, you are using node modules, but strictly speaking you are not writing a node app. The code that you write is executed inside JavaScriptCore and so doesn’t have access to the UNIX-like API from node.

This can make it a bit confusing about whether you can or can’t use a library from NPM. This also gets a bit more tricky, for example your tests are running inside node. So, it’s fine for your tests to use all of those APIs and libraries, but not your app’s code. So far, from my experience this hasn’t been a problem, in part because of how we use React Native (mainly API -> UI). For example, I researched all of this during the creation of this post, as I hadn’t really noticed the mismatch during active development.

JS Tooling

Facebook’s tooling is 👍. They have an IDE-like text editor called Nuclide, which is built on GitHub’s text editor Atom. If you’re using the default setup for React Native then you’ll probably have a good time with it.

We opted for using TypeScript to provide a type system to our React Native - I covered why inside Retrospective: Swift at Artsy. It’s got substantially easier to use TypeScript with React Native since version 0.45 includes work from Artsy and futurice making it possible via config settings alone. The alternative to TypeScript is Flow, which is also a great choice.

We choose TypeScript because of how well VS Code and TypeScript integrate. It provides an Xcode-like level of integration. Which, IMO, is a high baseline for expectations. It’s definitely less polished, but it’s Open Source and has substantial monthly releases - which is a very fair trade-off to me.

The node community is great at automation; we have code formatters and language linters that will auto-fix your code as you press save. We have pre-commit and pre-push hooks that are set up automatically when you start using the project. It means you spend less time thinking about trivial details that add up. It’s wonderful.

We use the debugging tools built into Chrome for our React Native, instead of something like LLDB. It supports all of the kinds of runtime introspection you would expect from Xcode.

Testing

Testing was never a priority in the iOS world. I feel like it’s always getting better with each Xcode version, particularly the change in Xcode 9 which allows tests to run in another simulator without turning off your app.

We really put a lot of time and patience into our native testing on iOS. Coming from that world, to the absolute ease of testing in the JavaScript world is pretty breath-taking. Check out my coverage of Jest’s features.

There are two ways to write tests for your React Native code: in process and out of process. E.g. from the JavaScript side, or in native side.

-

JS side: Choice of many Open Source test runners, built with hundreds of contributors involved in multi-year test runners.

-

Native side: Probably one or two people making XCTest, one person trying to get some improvements in Xcode each year. Semi-closed source.

We tried out a few native tests, but very quickly we stopped running them. Mainly as we were spending most of our time in a JavaScript environment, so tests would need to run in Xcode. As we don’t need a Mac to run our tests, we can use linux CI servers and get 3-4 minute CI runs.

Deployment

This one is a bit tricky to get your head around at first. React Native is a client-side native library that you don’t make source-code changes to, which interacts with the JavaScript that you bundle with the app (or use the React Native Packager at dev-time.) The JavaScript part of your application is just a file that can be updated, amended or fixed at any time.

This is not dynamically swizzing or fishhooking methods, you can ship new JavaScript code to your app which can interact with the exact same version of your compiled React Native library. The swizzling, and arbitrary native code changes are the problem that caused app store rejections early in 2017. React Native wasn’t the cause of those rejections.

The “deploy my JS anytime” idea is a little bit tricky though, because you can expose native code to your JavaScript. By exposing new functions, you end up with a “versioned bridge” where you make sure that the native functions your JavaScript expects actually exist. So you need to keep track of when you can update the JavaScript and the exposed native functions.

This is what makes it possible to ship bug fixes to your app as fast as the web. We use this, but only for admin users. They can choose the JavaScript for any commit on master, or any active pull request inside a beta version of our app. We don’t ship bug fixes to deployed apps, but we use this ability to provide a simple version of Testflight for our JavaScript code.

Our app release cadence is still about a month long, moving to React Native hasn’t changed that. We’ve automated the entire process, so it’s a cultural artifact rather than technical. So a day or two for the App Store review is fine, ideally our betas should be getting longer than that for testing.

Doing it right per platform

I’ve used the term cross-platform quite flippantly in this article to describe code that can run on many platforms. We’ve tried thinking of it as React Native gives us the ability to think in cross-platform terms. We now have most of our app’s root view controllers in React Native, which means we could make a pretty simple Android app re-using that code with a pretty small amount of effort.

We don’t though. The apps we make need to fit the platform and feel like the best experience you can get, when you’re potentially buying a > $100,000 artwork. We’d need an Android engineer with a lot of experience to work on the app, they’d need to be able to work on React Native for Android when we hit roadblocks and to provide useful context on how the app should feel. BTW, if this is you - get in touch (orta@artsymail.com) ;).

We already have some cross-platform code to get us started - but it won’t feel like the app we want to create until there is native code to take that React and make it shine.

So, where does the cross-platform aspect come from? For most users of React Native, native development has always been unavailable to them, and now it’s not, because React Native has lowered the barrier to entry. This means many people are aiming to make cross-platform React Native apps that are entirely in JavaScript (see Create React Native App.) They are just trying to get something shipped, which could be different from what you the reader are probably doing. As a native dev, you’re probably more interested in making something really fit the platform and shine. Lots of probablys, yes, but it fits the questions we’re being asked.

Both aspects of this are reasonable. React Native will let you do both. While React Native encourages you to think entirely at the V in MVC only, we still structure our React Native into UIViewControllers and still support unique iOS features via native code.

One place where this difference in perspective shows up is with navigation. In iOS it’s pretty straight forwards: use UINavigationController. For React Native, it’s actually really tricky, check out this issue where I write up all the trade-offs for the current set of APIs. Some of this is just a statement that figuring out the right abstraction is hard here, the other is that a lot of big apps are also at the same size as ours with ~2 years of React Native adoption.

Create React Native App

One of the biggest projects to happen in the React Native world in the last 6 months is Create React Native App (CRNA). This is the “super easy to get started” React Native experience.

Remember that most of the people coming to React Native are web developers, and the idea of writing Objective-C/Swift/Java to them is unappealing. CRNA actually removes the ability for you to write native code, and trades that with letting a company called Expo do it for you.

Expo are a pretty new VC-backed company, whose work is entirely open source. They’ve done a lot of foundational work in the community, and as individuals they are well respected for contributions to React Native the library - and a bunch of related libraries. You can use the Expo app from the App Store to run your CRNA project on any iOS/Android device instantly, and the app has a lot more baseline UI components to work with than React Native does on its own.

With CRNA you are giving up control of the native side, but gaining a lot on the ease-of-use side. CRNA doesn’t force the project to stay this way though, you can eject your app from using Expo and start adding native code to the app.

Why did I even mention this? Well, if you’re looking at React Native for a greenfield app (e.g. something new), CRNA may be your best option. When you’re getting started, less options is better, and this is the optimal setup according to the React Native team.

Animations

A question which regularly comes up is “How can React Native handle animations?” - at this point the answer is “well enough for 80% of all apps, it’s enough for ours.”

There are two primitives for animation from React Native:

Animated- This is a fine-grained API for handling changes (we use this in our buttons and view transitions.)LayoutAnimation- This API feels a little bit likeUIView +animate:- in that you can tell the layout engine that the next update should be animated instead of replaced. (we use this to handle view expansion)

These provide enough for most use-cases, but there is a more direct API and a few more JS-level techniques that you can use if you are really starting to feel like you’re dropping frames inside a specific animation.

The long-term aspects of React Native

What if Facebook stop maintaining React Native? Today it obviously doesn’t look like it, but if you’re talking the next 5 years - maybe it’s not that rosy. The JavaScript world moves real fast, 5 years ago React didn’t exist and Node still hadn’t had its big divorce and got back together.

Our perspective on dependencies has been that you should always own them in the sense that you have an understanding of how they work technically and culturally. This means for the larger projects, you should feel comfortable being able to make PRs back to the project, or feel comfortable that the vendor will fix bugs for you. The latter is not necessarily something that Facebook will be doing for you. They specifically call out that React Native is being built in the open, but that they are building and working on things that affect Facebook in production and then look at larger platform issues. You can get a sense of this by reading the React Native roadmap. These aims cover the rest of this year, and next year they’ll re-evaluate.

We’re pretty comfortable that if Facebook stop committing to React Native tomorrow, we (as Artsy) can continue to keep the project stable and at the same place across iOS releases. There’d be a learning curve, but we’re not the only company that’d be willing to do this too: AirBnb, Expo, Uber, Microsoft, GeekyAnts and Wix all participate at a very granular level and would probably make sure that the code you ship today will work with iOS 12 and so on - as they need that too. Should you rely on that? If you’re small enough then I think it’s reasonable. If you’re a medium sized company, I think you should have at least one engineer who understands and can deep dive into the dependency.

As a relevant example, Three20 had a very reasonable deprecation path, it’s just that a lot of people didn’t have the technical ability to migrate off. Frameworks like React Native and Three20 lower the barrier to entry considerably. The trade-off is that once you end up having to leave those frameworks, you have a pretty big learning curve to the baseline OS frameworks.

From my perspective, in Artsy there are only 2-3 projects that are 5 years old (Artsy was roughly founded in 2010) and I know a few of those are getting split into new apps. I’m not sure if we need to be looking that far ahead. Our keystone iOS app, Eigen was started in 2013, and has already gone through 2 complete internal transformations as our requirements and opportunities change. It’s very feasible that in 4 years we’ll be at a very different place again. We choose to not turn down something that so drastically improves our developer and speed for end users for that risk.

That said, Facebook indeed seem to be really happy with React, and React Native - making this question a useful hypothetical. Facebook are moving more big projects to use it internally, and there is a great discussion on how that is ongoing in this React Conf keynote from Jing Chen.

Performance

Your app is now running a lot of its code in JavaScript, isn’t that slower? It’s definitely true that your JavaScript will not be as fast as Objective-C or Swift. We haven’t benchmarked our before/after view controllers because it’s not a fair comparison, we switched from REST to GrahpQL at the same time. Our networking time was reduced so drastically, that it’s hard to talk about the JS vs native performance.

However there are a few advantages to running your app in JavaScript:

- There is no main thread, so you cannot block the UIKit UI thread

- There is no need to recreate JSON into native representations

- A lot of the hard work in React Native (layout, view manipulation) is done natively and in its own off-main thread

- For critical code, you can move to native, we did this for our image thumbnails

One place that doesn’t feel good writing in JavaScript is scroll events. This code has to generally be performance critical. This affects you when you want to have fancy transitions in your view controllers, however the animations API uses native code and with some careful consideration it’s very feasible to re-write those scroll events into a declarative API.

Sometimes you can look for better abstractions in React Native, the new ListView component provides quite a lot of the behavior you might want to use scroll events for, other times you may want to outright create a native view and then expose that as a component.

We found that the majority of our view controllers do a lot of work on init, then generally don’t do any more heavy lifting. So aside from our custom image thumbnails, we’ve not hit a point where we’ve had to move any code to be native in a year and a half.

Facebook patent clause

Facebook used to have a custom BSD license for their OSS projects like React and React Native, so you’ll still read comments about how you can’t trust those projects due to these patent rights in the license. In 2017, React moved to MIT and in 2018 React Native moved to BSD. Now this is a non-issue.

React Dependencies

This comes up in every post we make on React Native, because it’s always worth mentioning. React Native has 51 dependencies, which when resolved comes up to around ~650 dependent projects. This is a lot of dependencies. Remember that the JavaScript ecosystem does not have the equivalent of Foundation, and so to create a standard library, you use dependencies.

A dependency can be as small as a single function, or as fully featured as React Native. So it doesn’t really help to know the number in terms of anything other than “it’s a lot”. In this case, it is just the culture of JavaScript and node to work in this fashion. It’s like if you had to ship your version of Foundation and Cocoa with your app, instead of relying on the ones built into the OS. First you’d have to pay the memory and load time price for it in your app, and then you have a bazillion dependencies you don’t need like iAd or SpriteKit.

These unused dependencies can be removed at deploy time, but React Native is not at this point yet.

Places where React Native hasn’t fit for us

My first draft had notes on some of our mobile apps where we thought it might not fit. After some discussion, we changed our mind. So then our answer: Nowhere.

Note though, the types of apps we create are exclusively API driven, with a unique visual style which totally covers the exposed UI surface. React Native is a great fit for this kind of app.

Our main app Eigen, is a UIViewController browser, and React Native components are just one type of UIViewController that can be browsed. Nearly every UIViewController is the representation of an API endpoint, so React Native + Relay is a great match.

I used to say that our Kiosk app, Eidolon, might not be a good fit because of its reliance on handling a credit-card reader and that the app was good fit for being a storyboard-driven app. However, I’m not so sure about this anymore.

The project React Storybooks is not a direct replacement for storyboards, but as a live-programming/prototyping environment it’s 👍. The credit-card reader is already wrapped into a Reactive paradigm, going one step further and making it a JavaScript EventEmitter isn’t a big-jump.

Our tvOS app Emergence could probably be re-written in a week at this point. Is it worth a re-write? No. If I had to write it from scratch, would I use React Native? Probably, but it would depend on how stable tvOS support feels.

Our oldest app, Energy, is an app for keeping your portfolio of artworks with you at all times. Again, API -> UI. It’s an app which currently has a lot of demands on running offline. This is the only part that used to make me feel a bit unsure what that could look like with respect to moving the interface to React Native. However, changes to the Relay ecosystem which could allow us to create a simple Core Data backend, have reduced those worries.

When to choose React Native?

React Native provides a cross-platform API, and so it can fall into a watered down version of the API it abstracts. This means that it can be a bit more work than normal to use obviously iOS-specific features like ARKit, NSUserActivity, CSSearchableIndex or UIUserNotifications.

I say more work, because you definitely can still use them, but that transitions between your React code and your native code will require a bit more work than had you always been writing it natively.

That’s not enough of a downside to contrast against:

- A significantly better way to handle state and user-interfaces

- The potential to write code that is cross-platform, and also share ideas with the web

- An open development environment that respects your time

Especially when there is an Xcode project which you can use to do whatever you want with, you just need to learn how to jump back and forth between the two worlds.

React Native is a great fit for apps that:

- Are driven by an API, or an obvious state-store

- Want to have a unique look and feel

Here’s the final thing. When React Native was proposed as an option for us, the majority of our mobile dev team were not exactly excited at the prospect of using it. As we grew to understand the positive changes it was bringing for us, and our users, I was really happy that Eloy was willing to say “I think this could work.” Ash’s experience feels similar.

It’s less risky now, but it’s obviously a big dependency inside your app. Ideally, someone in your team should be able to feel comfortable reading, and potentially fixing code inside React Native for the platforms you ship.

Integrating into an Existing app

If you’re thinking of adding React Native to an existing app, first read on emission. Our usage of React Native is that it offers a series of components which are consumed by our app as a CocoaPod. This CocoaPods exposes UIViewControllers which can be used anywhere inside the app. This is the probably same pattern Airbnb, and Facebook use.

After you’ve read post, check out AirBnB’s experiences in this video and Facebook’s in this video.

Greenfield

I’d recommend to start with a CRNA app, it’s a good starting point. I would feel safe that you can eject out of the environment provided when the app becomes complex enough to warrant native code.

Wrap-up

This is the right place for a big call to action, where I declare that React Native is the future for all development and that it fixes all problems. I’m not going to do that. I think React Native is definitely the right choice for our team, and there are many apps that could have been created faster and cheaper by using React Native.

It’s safe to say we all were initially put off by JavaScript, but TypeScript has grown to be my favourite language, knocking Ruby off that pedestal. There’s potential that could change but we can only live in the present.

For us, React Native is a well thought out library, that can really help build better products when you understand the right way to apply it. It can help you be cross-platform on mobile, but also cross-platform with the web. For example, our React Native project has a sibling project on the web with the exact same setup, so any improvements in one move to the other. Which was unimaginable 2 years ago. We can truly consider sharing logic and ideas with the web.

If you’re considering a new app, or a grand re-write, React Native should be considered as one of your options.