Email! Electronic mail! What a concept! Like many companies, Artsy has built products on top of email, but this is a decision that (like many companies) Artsy periodically regrets. But overall, our email systems work well!

But what about when it doesn’t? Well that’s what today’s blog post is about: what happens when things break and you don’t know why?

I have learned a lot since my first on-call shift, but going on call still gives me a little stage fright. As I start a shift, I’m on the look-out for things that might break, and soon after starting a recent on-call shift, “breaking” is exactly what things did.

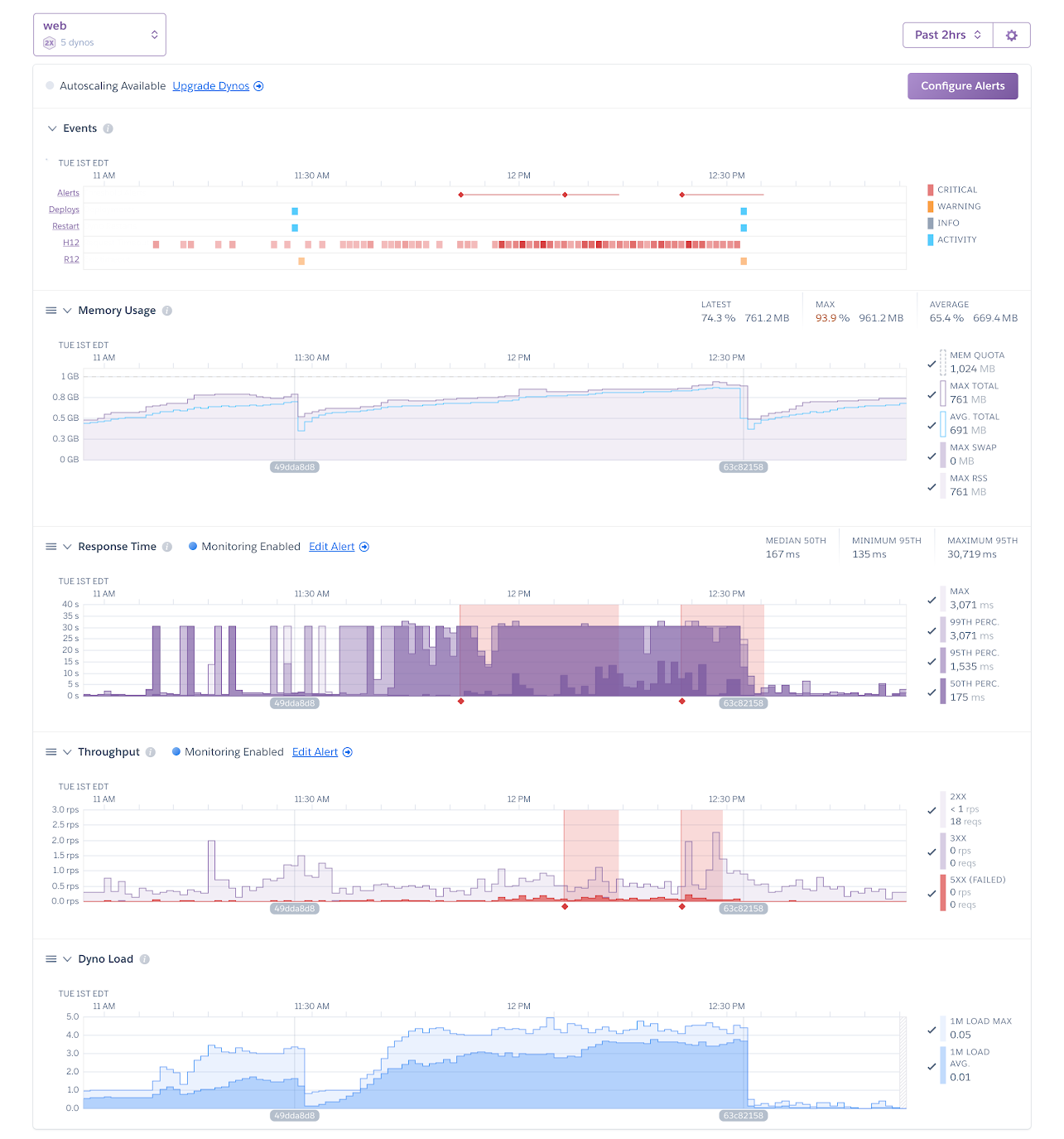

We got an automated alert on Slack that one of our email services, code-named “Radiation”, had really high response times. We then received an alert that too many requests to Radiation were failing completely. Yikes. The next twenty two hours was a deep dive into Heroku, New Relic, Rails, and PostgreSQL, all to isolate the problem and produce a solution.

The nice thing about email, as a protocol, is that it’s based on a store-and-forward concept. That means that if a message delivery fails, email servers will try again later (typically with an exponential backoff). SendGrid, our email processor, has built their REST API around this same store-and-forward concept. While the Radiation server was unresponsive, SendGrid wouldn’t receive successful HTTP responses from the webhook deliveries, so it would attempt to re-deliver the failing emails later. Email deliveries would be delayed, but the emails themselves would not be dropped. We wasted no time addressing the problem, but we were also confident that once we fixed the issue, the data would be okay.

After the alert, Ashkan (Radiation’s point-person) and I communicated with our colleagues (engineers and affected non-engineers) about the problem. With the help of Chung-Yi, we began investigating the immediate problem (with a focus on mitigating it, rather than necessarily fixing it). Oh, we tried it all: spinning up more Heroku Dynos to handle requests, increasing concurrency on the individual Dynos, restarting Redis and PostgreSQL stores. Each time, things would work briefly before the Radiation API would begin timing out again. More accurately, the requests sent to Radiation were taking longer than the Heroku router was giving them (30 seconds) before the router gave up and timed out the request. We started examining the Radiation code and database (keeping our ion the prize: mitigation).

Ashkan investigated slow database queries. We added new PostgreSQL indexes to speed up queries, and restructured others to avoid expensive joins. Unfortunately, all this accomplished was extending the time after a Dyno reboot that things would work (before beginning to timeout again). Because Artsy stores emails as encrypted-at-rest, it was difficult to pinpoint which exact message could be causing the timeouts. And Radiation itself didn’t have much in the way of logging, which would normally help us debug the problem.

It was frustrating to try to fix something but only manage to improve how long it took to break again. We had enhanced Radiation’s performance to the point where it was taking 10 minutes after a Dyno reboot to begin timing out again, up from 30 seconds at the beginning of the incident. Despite an afternoon and evening spent trying to fix the problem, we were stuck. We decided that the best course of action was a good night’s sleep; we would ask for help in the morning.

The next day, Ashkan and I got up and atom to address the problem. We brought my on-call partner Devon up to speed, detailing the incident symptoms and what we had tried so far. While Devon and Ashkan worked on additional logging and new timeout strategies, I took another approach.

Artsy has been moving to DataDog for server performance monitoring, but Radiation was still using New Relic. My background is in iOS app development and I had never really dug into New Relic before, but I am very experienced at profiling iOS applications, and the Ruby and Objective-C runtimes have more in common than they have have differences. I used New Relic to profile a production Radiation Dyno for five minutes and, to our collective surprise, we found that more than 90% of CPU time was being spent in an innocuous function of a dependency, the open source library Griddler.

Artsy uses Griddler to parse and sanitize emails that we receive from SendGrid. Griddler contained the problematic code, which was responsible for parsing email responses from threaded replies. So if an email body received by Radiation looks like this:

This is the most recent reply in this email conversation.

On September 28th, 2019, Someone Else Wrote:

[The rest of the email thread]

Then Griddler parses out the string “This is the most recent reply in this email conversation.” for Radiation to process. This is really important because some of the threads in Radiation are thousands of emails long. In fact, I learned that Radiation has Artsy’s largest production database.

Griddler does this processing via regular expressions. Ashkan had the insight to look for existing issues from other Griddler users who ran into similar problems, and to our delight, we found a pull request that appeared to address the exact issue that we were having.

It turns out that emails with large amounts of repeated newline characters would totally stall Griddler’s regex. Heroku’s router would timeout any request after 30 seconds, but would leave the Ruby code churning on that regex. That would leave the Rails server unable to respond to subsequent HTTP requests, causing more timeouts. And because of email’s store-and-forward nature, SendGrid would begin sending more problematic emails pretty quickly after any Radiation reboot. A small change to add a regex group was all that was necessary to fix the issue.

Phew! We forked Griddler to Artsy’s GitHub organization and applied the change from the pull request. We were concerned about security implications of using a different regex, but my previous work in regular expressions helped me vet the change. We pointed Radiation’s Gemfile to Artsy’s fork and deployed the change.

Then, we waited. Would the system start timing out again? It took a half hour for any of us to breathe a sigh of relief. But things appeared to be stable: response times were normal and Dyno load dropped precipitously. Our Curie worked. (Okay, enough radiation puns.)

During our weekly incident review, Devon guided the rest of our team through our incident response and what we learned. Radiation is now in a much better state, so that future problems will be easier to track down. We responded to the Griddler pull request, encouraging the maintainers to merge the commit so other teams would avoid this problem. The incident review meeting explored a number of options to mitigate future issues, including migrating Radiation to our Kubernetes cluster, and Sam (our VP of Engineering) suggested writing this post. So here we are.

Ashkan also followed up with peer feedback for Devon, Chung-Yi, and myself. In part, it read:

It’s rare and odd to say dealing with incident was fun, but with your help it actually was productive and fun.

Which, honestly? One of my proudest accomplishments at Artsy.

In the end, we solved the problem and restored access to our email systems in under 24 hours. We kept our cool, we communicated effectively with our non-engineering colleagues, and we learned a lot. What more could you want from a Radiation incident?