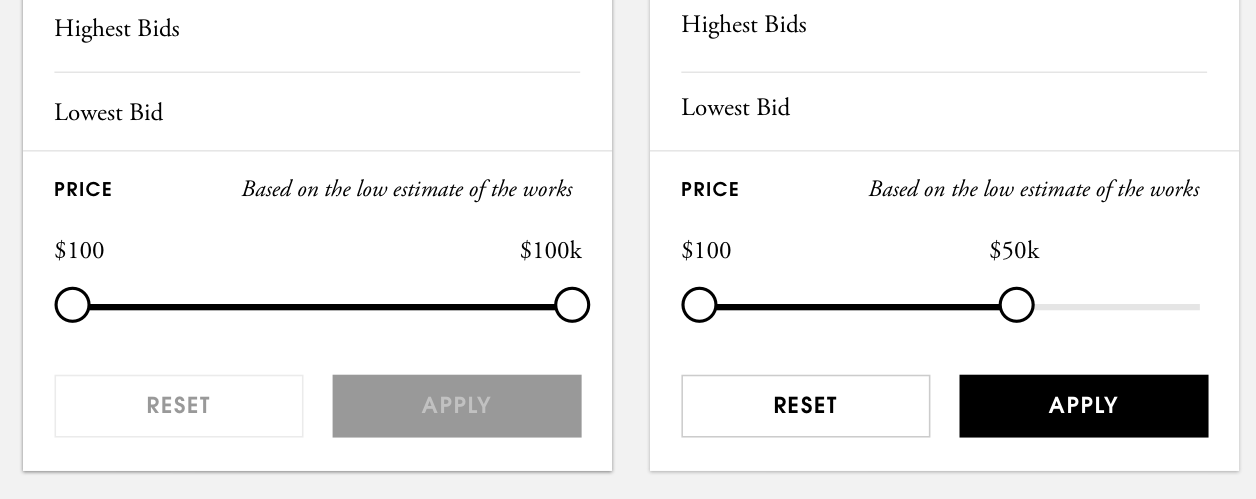

Let’s take a look at the day in the life of an open source citizen: me. On our app, I was given an issue that would allow users to refine what kinds of sale artworks they were looking at, and it included this awesome slider control so they could set min/max price ranges.

</div></div> <div class='meta-container'><header> </header></div><div class='date-container'> </div><div class='content-container'><div class='entry-content'>

<div class='meta-container'><header> </header></div><div class='date-container'> </div><div class='content-container'><div class='entry-content'>

Nice.

But iOS doesn’t have a slider like that built into UIKit, so I headed to CocoaPods.org to find something that would work for me. Searching for “range slider” yielded a bunch of results, and I looked through three or four of them.

I picked this one because it did almost exactly what I needed, provided a reasonable level of customization, and had a history of development leading up to a recent v1.0.

But I said it did “almost exactly” what I needed, which meant I’d have to modify it. At this point, many developers either look for a different library or abandon the idea of using an existing library altogether and invent one themselves. That’s a shame, because it’s almost always faster and easier to improve an existing library than it is to build your own.

So let’s step through what I did to modify this library for my needs. First, I checked to see if there was an issue for my feature already opened on the repository; maybe someone else had tried this, and I could benefit from their experience! That wasn’t the case, so I forked the library to my personal account and cloned my fork locally. Now I can modify the library’s code and commit it to my fork.

Next I add the library to my Podfile, but I’m clever about it.

pod 'MARKRangeSlider', :path => '../MARKRangeSlider'

This tells CocoaPods that I’m working on the pod, and, it is stored in a local directory (the one where I cloned my fork). This makes it a “development pod”, so that the files in Xcode are actually the ones I’ve cloned locally.

This is a really important, but subtle point. Normally, CocoaPods downloads copies of the files and stores those copies, but in this case, it refers to the existing files. It doesn’t copy them at all: any changes I make to the library while working on my app are to the files I cloned. That means they can be easily committed and pushed up to my fork.

That’s exactly what I did. I made my changes from within the app until I was satisfied, and pushed them to my fork, then pointed the Podfile to my fork of the pod.

pod 'MARKRangeSlider', :git => 'https://github.com/ashfurrow/MARKRangeSlider.git'

Nice. At this point, I continued on as a developer, running a pod install to download the forked library with my commits as usual. I finished building the feature and PR’d it using my fork.

I could’ve stopped here, but that’d be a shame. Someone else might want the same changes I made, and I should submit them back. I opened a PR on the library to contribute my changes back, and I made sure to explain why my changes were necessary. Because our app is open source, I was even able to link to our PR to show the library author how their work was being used.

The next morning, I woke up to find my PR had been merged, and after the author pushed an updated version of the library (including my changes), I updated our app’s Podfile once more.

pod 'MARKRangeSlider'

Then ran pod update MARKRangeSlider so it would update just that pod, and point it to the new release. I re-ran the unit tests to make sure I hadn’t broken anything, and PR’d the change.

This sounds like a lot, and having written it all out, I guess it is. But it’s a series of small steps, not big ones, and I’ve worked like this long enough that it’s second-nature to me now.

I believe that using existing open source libraries is almost always better than writing your own, and I believe that improvements made to open source ought to be shared. Those beliefs shape my behaviour as a developer, and as a person.

Making your first contribution to a project may seem scary, but we all start somewhere. It gets easier, and in time, you will become a paragon of open source citizenry.