The website is finally back up after crashing hard for 4 hours straight.

Recently AWS decided to reboot a few of your servers for a critical update. It didn’t seem like it was going to be a big deal, except that the schedule was only accommodating if you were in the Pacific Northwest. The first reboot took out a secondary replica of our MongoDB database. Unfortunately the driver handled that poorly and spent the first 400ms of every subsequent HTTP request trying to reconnect to the missing instance. That server came back up, but failed to find its storage volumes because of a human mistake in a past migration and the alerts were mistakenly silenced by someone monitoring the system. A few hours later the primary was being stepped down and rebooted, sending the driver into panic over another bug. The site went down.

None of this was obvious while it was happening as the rate of automated alerts grew. Engineers communicated to the team that they are actively focusing on bringing the systems back up. This helped to fend off a large amount of instant messages, e-mails, texts and phone calls from various people on the team that were in the middle of demoing something to a very important prospective customer on the other side of the planet. It was also the middle of the night in New York.

Now that all the systems are back up, lets write a detailed outage post-mortem.

Whose Job is It?

In a small or medium-sized company, the most senior engineering manager, CTO, VP or Head of Engineering should be writing an outage post-mortem. It’s their job and responsibility to acknowledge, understand and explain what happened. Focusing attention away from the individual contributors allows the team to learn from the mistakes and address the root causes in time without the unnecessary stress or pressure during a crisis.

Recipients

The post-mortem audience includes customers, direct reports, peers, the company’s executive team and often investors. The e-mail may be published on your website, and otherwise goes to the entire team. It’s critical to bcc everyone. This is the equivalent of a locked thread, avoiding washing the laundry in public: one of the worst possible things to see is when a senior manager replies back pointing an individual who made a mistake, definitely not an email you want accidentally sent to the entire company.

I usually begin my e-mails with Team (on the bcc), ….

I also bcc myself and label the e-mail “Outages”, to be able to easily find the incident history next time around.

Outage Email Subject

Post-mortem subjects should include a date and a duration. This gets right to the point and offers a summary of the impact.

Outage Summary

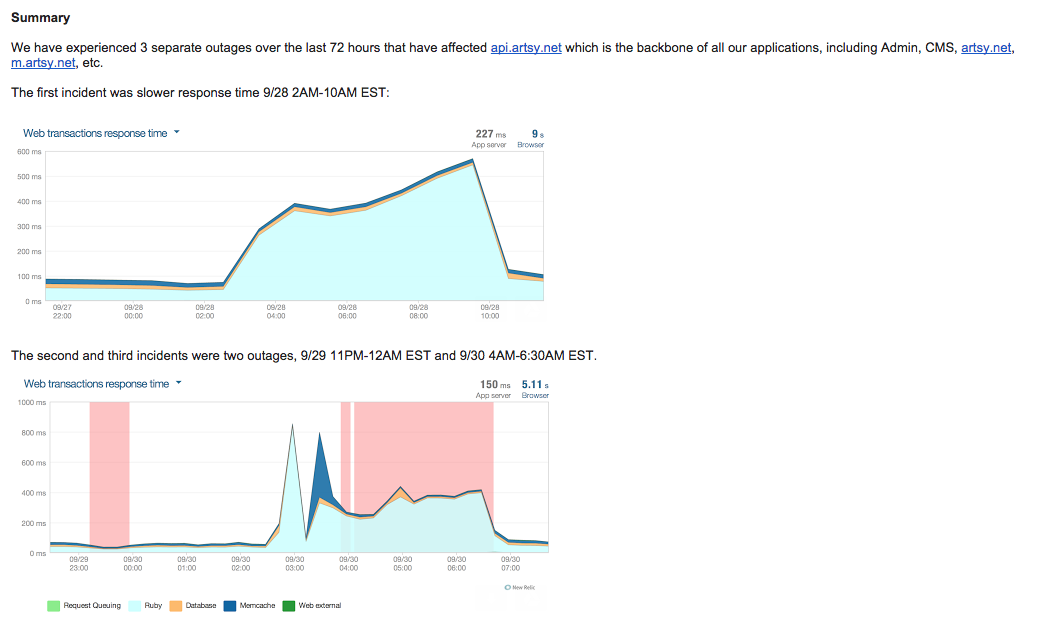

The outage e-mail begins with a summary, a slightly expanded version of the subject line. Many people won’t read the details, so include graphs. These should tell the same story as the description of the outage. I use NewRelic’s.

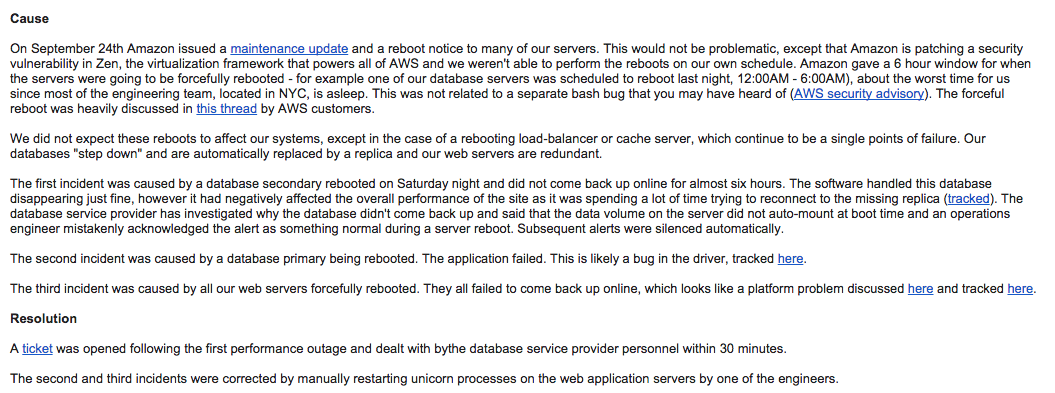

What Caused the Outage

Explain what caused the outage on a timeline. Every incident begins with a specific trigger at a specific time, which often causes some unexpected behavior. For example, our servers were rebooted and we expected them to come back up intact, which didn’t happen. Furthermore, every incident has a root cause: the reboot itself was trigger, however a bug in the driver caused the actual outage. Finally, there’re consequences to every incident, the most obvious one is that the site goes down.

How was the Outage Resolved

Now that the timeline of the outage is established, we explain what actions took place to resolve it.

The Post-Mortem

The post-mortem answers the single most important question of what could have prevented the outage.

Outage History

To most humans that encounter bugs, it may seem like your systems have failures all the time. It’s important to educate everyone that an outage is much more than a bug and that it hopefully doesn’t happen frequently. Provide a history of outages, referencing the last one.

Don’t Bury It

A few final words. Despite how painful an outage may have been, the worst thing you can do is to bury it and never properly close the incident in a clear and transparent way. Most humans come together in times of crisis and communication around outage post-mortems, in my experience, has always been met with positive energy, understanding comments, constructive suggestions and numerous offers to help.

Comments