At Artsy we’ve been building Node.js applications that share code and rendering between the server and browser. We’ve seen many benefits from this – pages load faster, we can optimize SEO, developers are more productive, and JavaScript coding is just an overall better experience.

Today we’re happy to announce Ezel, our open source boilerplate we use to bootstrap our Node projects and the various node modules that built up to it.

In his article, Isomorphic JavaScript: The Future of Web Apps, Spike Brehm from AirBnB describes this growing trend well and we’re excited to be a part of it. In this article I’ll tell Artsy’s story of moving from a single monolithic application to modular Backbone apps that run in Node and the browser and consume our external API.

Growing Pains

Artsy started as a mostly standard Rails app almost three years ago. In these beginnings we were wildly productive and owe a lot of props to this great framework. However as time went on we started to deviate from the conventional Rails path until we were hardly leveraging much Rails at all. To support an early iOS app we used Grape to build an API. While building our API we wrote a lot of client-side JavaScript and soon integrated Backbone for organization. Eventually we cleanly separated our project into a single page Backbone app talking to our API all on inside of this original repository.

We knew we were outgrowing this monolithic project because we had some clear problems…

- Slow initial page loads because of lacking server-side rendering. Twitter describes this problem well.

- Slow following client-side renders because of downloading large asset packages without clear ways to break them up.

- SEO issues like building escaped fragment pages in Ruby on the server while our users saw what JavaScript rendered on the client.

- Maintaining duplicated Ruby/JavaScript code such as templates, date libraries, etc.

- Very slow and brittle tests. We had a massive integration test suite consisting of over 3000 Capybara tests that took hours to run because we lacked good JavaScript testing tools.

- Poor mobile experience from trying to responsively scale down a large single page app with bloated and unused assets.

- Slow asset compilation, server boot, and general build times. Productivity suffered greatly as more code was added to the same monolithic project.

There’s Got to Be a Better Way

A monolithic app that treats it’s client-side code as a second class citizen was clearly not going to scale. Our poor mobile web experience was a good candidate to try something new. So we started building a separate mobile optimized website (m.artsy.net).

Some goals became clear:

- Better client-side tools from JavaScript testing to package managers.

- Share rendering code server/client to reduce duplication and optimize initial page load.

- Flexibility. We needed a way to divide our app into smaller chunks with smaller asset packages.

Choosing Technology

Node was a clear choice because it made sharing rendering code server/client possible where other languages and frameworks struggle to do so. There were some existing Node projects that accomplish this such as Derby and Rendr. However, adopting these had challenges of their own including being difficult to integrate with our API, learning unnecessary conventions, or being early prototypes with lacking documentation.

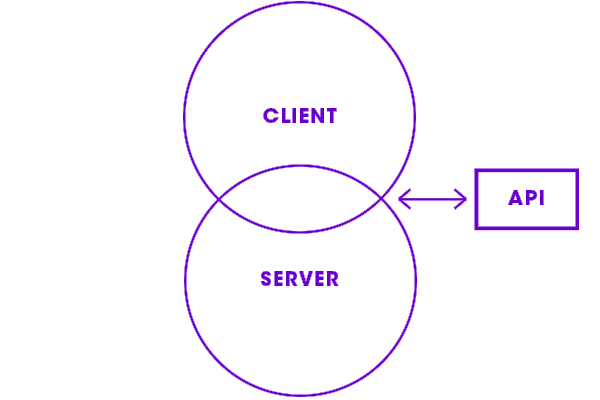

We wanted an approach that breaks our app into smaller, more flexible, pieces. Not all of Artsy needs to be a thick-client app, or even use much client-side JavaScript at all. Adopting an existing solution and combining most of the server and client into a shared abstraction seemed like an unnecessary black box. After trying many other frameworks we found a combination of lower-level tools to be a clear winner.

We open sourced this combination of tools and patterns into Ezel. Ezel is a light-weight boilerplate project using Express and Backbone for structure, and Browserify to compose modules that can be shared server/client.

Sharing and Rendering Server/Client

To share rendering code server/client we had to make sure our templates and objects being passed in to them could work the same server/client.

Sharing Objects (Backbone Models)

Browserify lets you write modules that can run in Node or the browser. Since Backbone is able to be required on the server out of the box, it’s easy to write models and collections that can be required on both sides with Browserify. However, there are two main speed bumps in doing this:

-

Backbone uses AJAX for persistence.

We needed a Backbone.sync adapter that makes HTTP requests server-side, so we wrote one and it’s open sourced.

-

Data from the server needed to be shared in modules that are used server/client.

For instance, our API is an external URL stored in an environment variable. We needed to use this variable in a module that will be required on the server and the client with Browserify. Bootstrapping data is a common technique to share data from the server by embedding JavaScript in the initial HTML and exposing that data globally to the client. To avoid exposing globals we open sourced a tiny module called sharify.

Sharing Templates

Browserify even lets you share non-JavaScript components server/client using transforms. To reuse our jade templates server/client it was a simple matter of using the jadeify transform.

All Together Now

With templates and models require-able server/client, sharing rendering code became much simpler. Below is an example using the same artwork model and detail template server/client.

Shared Backbone “Artwork” model to be required server/client:

``` javascript models/artwork.js var Backbone = require(‘backbone’), API_URL = require(‘sharify’).data.API_URL;

module.exports = Artwork = Backbone.Model.extend({

url: API_URL + ‘/api/v1/artwork’

});

Shared partial jade template used server/client:

```jade templates/artwork-details.jade

h1= artwork.get('artist').name

h2= artwork.get('title')

Full server-side page template including the partial:

```jade templates/artwork-page.jade doctype 5 html head title Artsy | #{artwork.get(‘title’)} body include artwork-details != sharify.script()

Route handler that uses the model server-side:

``` javascript app.js

//...

var Artwork = require('models/artwork.js');

app.get('/artwork/:id', function(req, res) {

new Artwork({ id: req.params.id }).fetch({

success: function(artwork) {

// Boostrap artwork data into sharify

res.locals.sharify.data.ARTWORK_JSON = artwork.toJSON();

res.render('artwork-page', { artwork: artwork });

}

});

});

Client side code that requires the partial template and model:

``` javascript client.js var Artwork = require(‘models/artwork.js’), ARTWORK_JSON = require(‘sharify’).data.ARTWORK_JSON, detailsTemplate = require(‘templates/artwork-details.jade’);

var artwork = new Artwork(ARTWORK_JSON); artwork.on(‘change’, function() { $(‘body’).html(detailsTemplate({ artwork: artwork })); });

## Developer Happiness

Not only does sharing code server/client let you easily optimize page rendering for fast page loads, but development becomes a lot nicer because we can reuse server-side JavaScript tools including...

### Package Managers

With Browserify we were able to use npm as a package manager for server or client-side dependencies. There are [other](http://bower.io/) [package](http://component.io/) [managers](http://jamjs.org/) for the client-side. However, because we were already using npm (and npm supports git urls), we could usually point to the project hosted on npm or Github without having to fork it.

For projects that don't support CommonJS modules (or npm), often one can still use npm and requires like so:

``` json

"devDependencies": {

"zepto": "git://github.com/madrobby/zepto.git#c074a94f0f26dc946f1c501f5f45d603adada44d"

}

javascript client.js

// Require the base Zepto library (attaches `Zepto` to window)

require('zepto/src/zepto.js');

// Attach Zepto's plugins

require('zepto/src/event.js');

require('zepto/src/detect.js');

// ....

Testing

Testing is light-years ahead because you can test all of your code in Node headless. I wrote an article on this a while back, and now with Browserify it’s even better.

Models, templates, and other modules that are shared server/client can be required into mocha and tested server-side without extra effort. For more view-like client-side code that depends on DOM APIs, pre-rendered HTML, etc., we open sourced a library called benv to help build a fake browser environment in Node for testing.

Modularity

We wanted to avoid a monolithic organization that groups code by type such as “stylesheets”, “javascripts”, “controllers”, etc.. Not only is this a maintenance problem as it makes boundaries of your app unclear, but it also affects your users because it encourages grouping assets into large monolithic packages that take a long time to download.

Instead, we borrowed a page from Django and broke up our project into smaller conceptual pieces called “apps” (small express sub-applications mounted into the main project) and “components” (portions of reusable UI such as a modal widget). This let us easily maintain decoupled segments of our project and build up smaller asset packages through Browserify’s requires and Stylus’ imports. For more details on how this is done please check out Ezel, its organization, and asset pipeline docs.

It’s also worth noting, to avoid CSS spaghetti we followed a simple convention of name-spacing all of our classes/ids by the app or component name it was a part of. This was inspired by a blog post from Philip Walton.

Success!

With this new architecture and set of Node tools we’ve seen enormous benefits compared to the pains of developing Backbone in a monolithic project with lacking JavaScript tools. Our mobile web experience is much better, we can render more content on the server for SEO and faster page loads, our test/build/deploy cycles went from hours to minutes, our developer on-boarding time went from days to minutes, and overall developer happiness has significantly improved.

It’s an exciting time to be developing JavaScript apps and we will continue to open source our efforts wherever possible. Thanks and follow us on Github!

Comments