I am a big fan of developer tooling, as spending time upfront on improving your process can pay a lot of dividends over time. I want to talk about one in particular: Paw. Paw is a native HTTP client with a bunch of features. I want to cover one that means that we can now introduce [AppName].paw files in our mobile projects, making it easy for us to discuss networking requests.

OK, what is Paw?

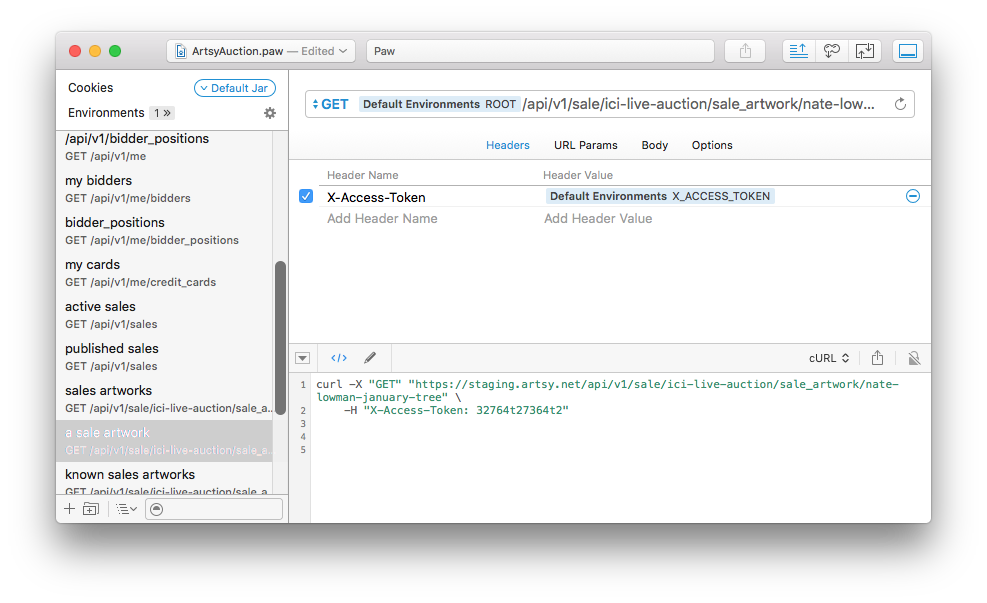

Paw is a tool that stores collections of API endpoints, along with all the metadata required to call them. We first started using Paw during the creation of Eidolon as a way to keep track of the auction-related API calls we would need to stub for Moya, an iOS networking library that required stubbed data. It made it easy for us to keep track of how all the different API routes work together, and to verify that we were doing things right.

</div></div> <div class='meta-container'><header> </header></div><div class='date-container'> </div><div class='content-container'><div class='entry-content'>

<div class='meta-container'><header> </header></div><div class='date-container'> </div><div class='content-container'><div class='entry-content'>

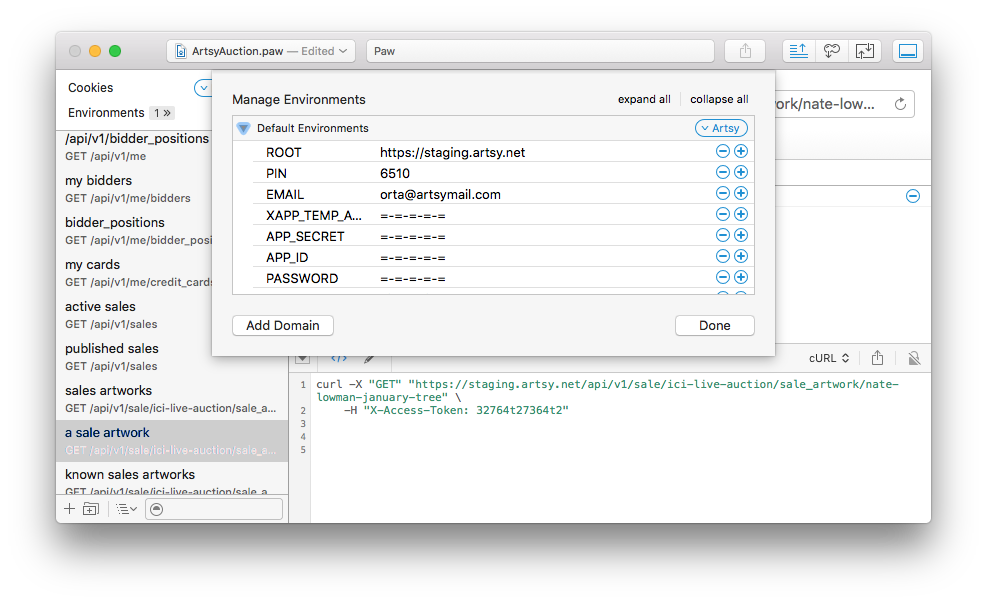

We used environment variables to keep track of things we wanted to change, but in using them this way we couldn’t publicise our Paw files, the real versions contained secrets that should stay secret.

The environment tooling made it easy to change the routes, users and settings easily, but were also the thing keeping us from being able to share the files in source. Because of this, we stopped using Paw to keep track of our routes as we had to ad-hoc share the file over chat.

A Second Shot

This week, roughly a year and a half later, I started work on a large project that I knew would involve using new networking APIs. So I took the time to look for ways to interpret what I was going to be working with. After exploring some alternatives, I came back to Paw, and discovered they had a new feature: Keychain integration. This stopped my search.

In our iOS projects, as they are all open source, we use CocoaPods-Keys to ensure that our development configuration secrets are kept safe and outside of the project’s source code. It stores the per-project keys inside a developer’s Keychain. This means they can be accessed from inside the iOS app, but also from the developer’s computer via a determinate location in the Keychain app.

~/d/i/a/energy (master) ⏛ bundle exec pod keys

Keys for Folio

├ ArtsyAPIClientSecret - [***********]

├ ArtsyAPIClientKey - [***********]

├ HockeyAppBetaID - [***********]

├ HockeyAppLiveID - [***********]

├ IntercomAppID - [***********]

├ IntercomAPIKey - [***********]

├ SegmentProduction - [***********]

├ SegmentBeta - [***********]

└ SegmentDev - [***********]

This means that we can use CocoaPods-Keys with Paw in order to use the same ArtsyAPIClientSecret and ArtsyAPIClientKey environment config variables. Great. This is almost enough to make the first API call to to get an access token.

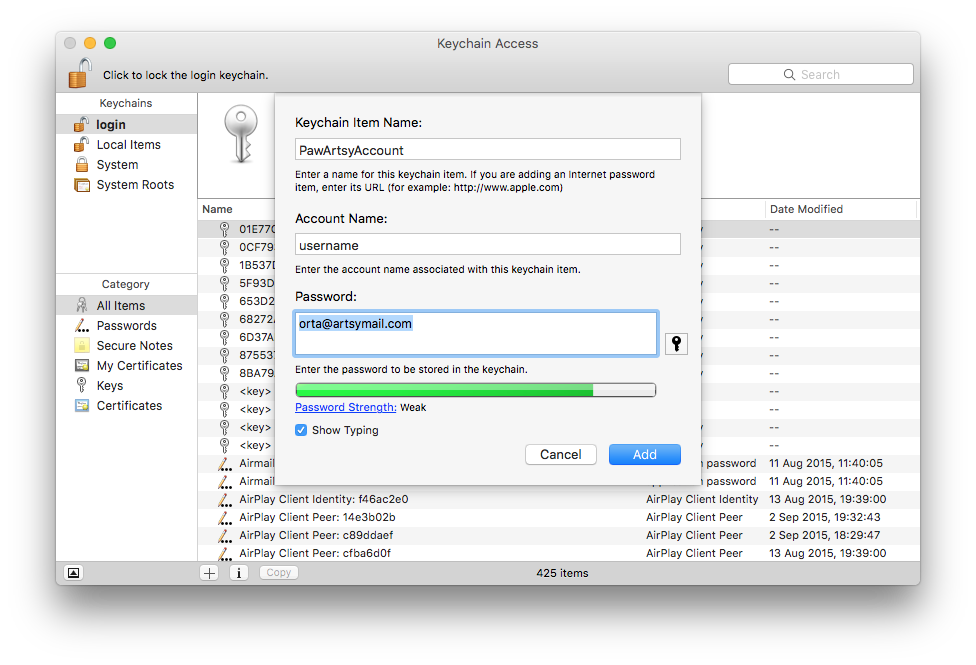

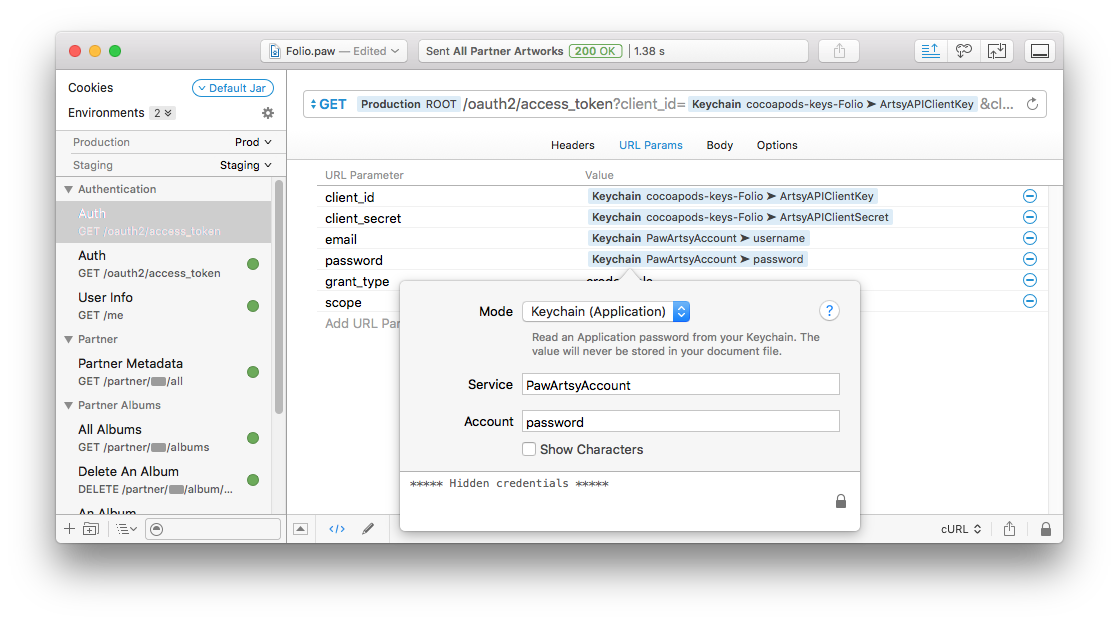

I re-used this idea to allow developers to have unique username and passwords. I created two more entries in Keychain, username and password. This is something that every developer using our Paw file has to do, otherwise Paw won’t know who to log you in as.

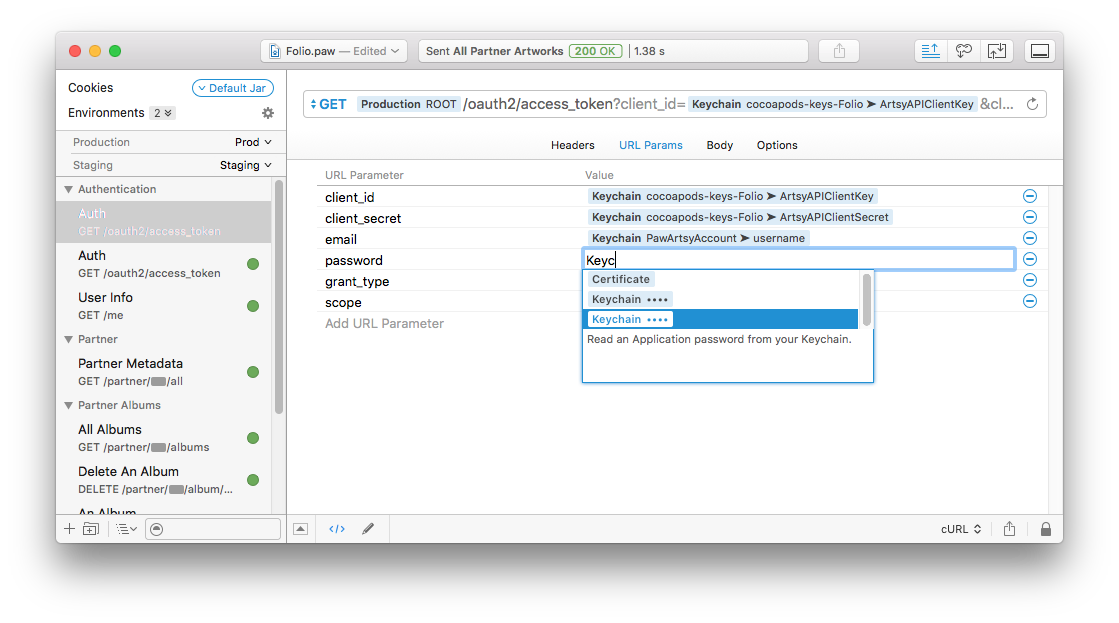

With these all hooked up, I could set up Paw to use all of our Keychain entities:

Tada! Now I can run my route, and I’ve got an access token to use with our API.

Route Resolving

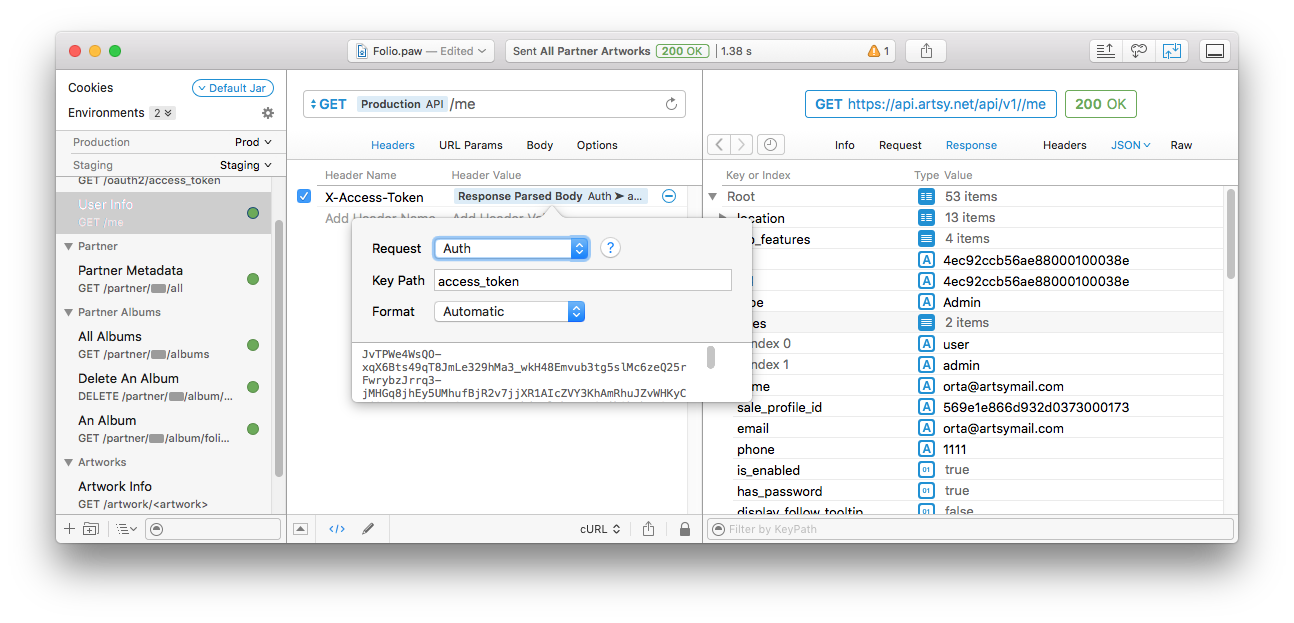

Automating the route to get an access token is the first step because Paw allows you to use the output of one route inside any new route. I’ll show you, then talk it through.

</div></div> <div class='meta-container'><header> </header></div><div class='date-container'> </div><div class='content-container'><div class='entry-content'>

<div class='meta-container'><header> </header></div><div class='date-container'> </div><div class='content-container'><div class='entry-content'>

I made it so that my new request ( for the route api/v1/me) passes in an header of X-Access-Token, with the value being the access_token from the route we just made called Auth. This means that when the token expires, it will automatically re-generate a new one and we’re never storing the token explicitly inside the Paw file. Our secrets stay secret, and per-developer - I don’t want to know other people’s passwords.

Once those two routes were set up, it was a matter of looking up what routes I would need and added them to the paw file for the project. I used the group system to make it easy to show / hide sections, and experimented with using environments to differentiate between staging and production servers. Not quite figured that yet.

Wrap up

It’s easier to talk about your API when any other developer can open this one file and shoot off requests at the same time as you. One of my favourite nice-touches is to be able to easily convert any request into a cURL command.

I am using this event as a reminder to myself that tools evolve, and maybe your first impression on a developer tool may require re-interpreting in light of software evolution.