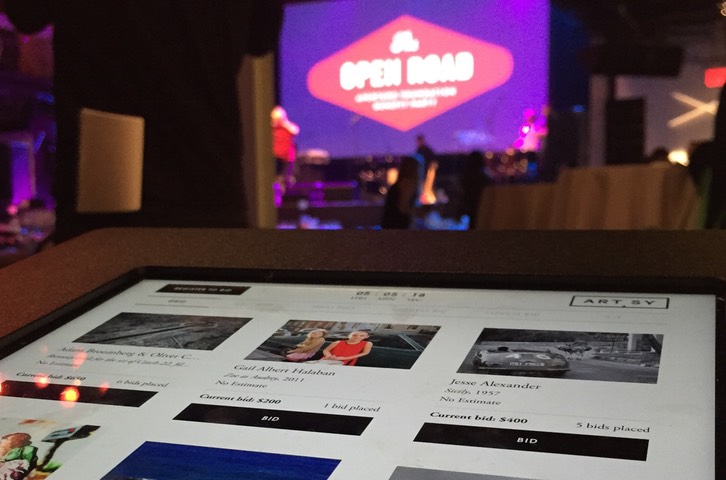

In the Summer of 2014, we began developing a bidding kiosk for the Artsy auctions platform (code-named Eidolon). Typically, the iOS team here at Artsy worked on two main apps: a consumer-facing iPhone app and an iPad app used by art galleries. For Eidolon, we followed Artsy’s standard practices for building our software and use GitHub issues as our canonical source for bug reports and feature requests. Many of the components used in our apps are open source, but the codebases themselves remain in private repositories.

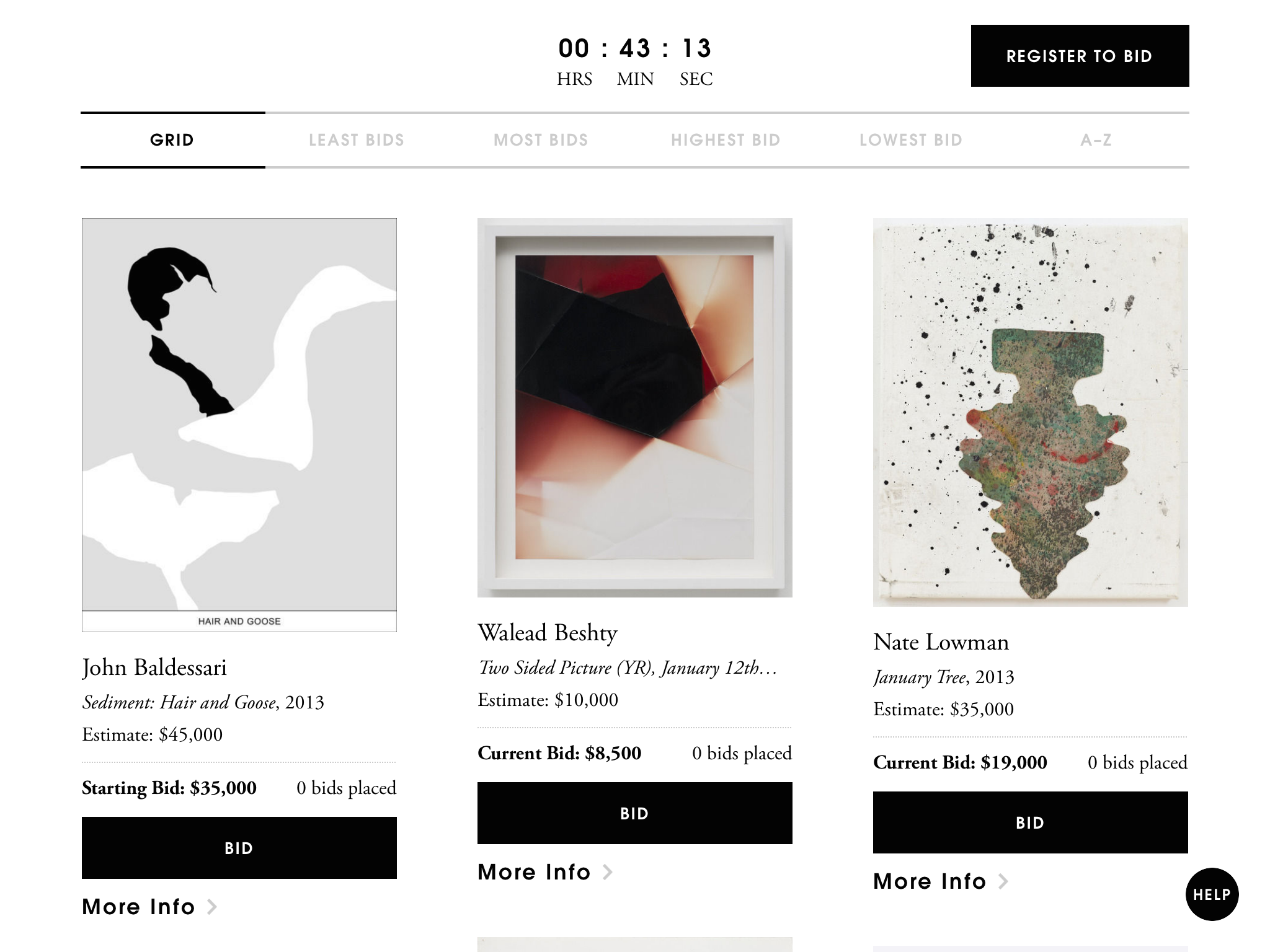

Initial planning for Eidolon began over the Summer. Our designer Katarina had the main features sketched out. I was scheduled to work on it at first, with Orta and Laura joining me near the end of the project. We had a rough scope: the app would be able to list artworks at an auction and allow prospective bidders to learn more about these artworks. The user would be able to register to bid and place bids using the Kiosk, including credit card processing for identity-checking.

An Idea

Orta and I met some friends over a weekend in Austria and, during our drive across the country, discussed the possibility of developing this new iOS app as a completely open source project. We were both excited about the prospect and had the support from dB to make it open. There were just some technical issues that would have to be addressed to make the Kiosk app an open source reality. For example, how would we restrict access to the app’s API keys? Developing Eidolon in the open would let us share what we’ve learned, a value at Artsy, and also allow us to easily ask for help from the community.

We were also together in San Francisco for Apple’s announcement of Swift. Following the announcement, there were lots of small pieces of source code published on the Internet that demonstrated some of Swift’s new features, but a large project didn’t really exist to show how iOS apps written in Swift don’t have to be moulded by outdated Objective-C traditions.

I wanted to write this app in Swift. After speaking with Orta, he said that as long as we could meet the deadlines, that would be okay. (Since this app uses enterprise distribution instead of the App Store, using beta versions of Xcode wouldn’t be a problem.)

More than just an app written in Swift, I wanted to build this app with functional reactive programming principles in mind. We would be using ReactiveCocoa any place that it made sense. While I had begun using it in our consumer iPhone app, it was mostly replacements of KVO code. This would be a fully “functionally reactive” app, a first for Orta and Laura.

So to summarize: our team embarked on a brand new project, developed in the open, using a new and incomplete language, built using a non-standard approach to functional programming, and using beta versions of Xcode. It was ambitious, but we were excited by the prospect of learning new things. I believed then, and do now, that Swift is the future of iOS development, and we love to be on the cutting edge (Artsy’s iOS apps are often testbeds for new CocoaPods features). There’s also an incredible demand for sample code written in Swift, so having a complete codebase written in Swift early in the language’s lifetime would be a significant contribution to the open source community.

Getting Started

The first steps were trivial. We examined our existing approach to iOS development and decided what techniques would be appropriate to use on this new project. Then, we identified tools that we needed to use those techniques. In some cases, existing tools needed to be modified to suit our needs. In other cases, the tools didn’t exist at all and we had to invent them.

Shortly after Swift’s announcement, Brian Gesiak began work on Quick and Nimble, a Swift-based testing framework and matchers framework, respectively. We would be able to continue using rspec-like syntax for our unit tests – awesome.

We use continuous integration on our other iOS projects and wanted to do the same for Eidolon. However, our usual CI provider, Travis, has historically not supported beta versions of Xcode – our only choice for CI would be Jenkins. With a basic Swift Xcode project in hand, Orta set up Jenkins on a Mac Mini in the Artsy office. This didn’t meet our needs for a few reasons. Primarily, getting the build to work from a command line was difficult with Swift and Xcode 6 – Orta spent quite some time getting it configured. However, we all sorely missed some of the great integrations that Travis provides, particularly with GitHub. During development, we technically did have continuous integration, but it wasn’t leveraged to nearly the degree that it could or should have been.

A large portion of our tests on our other iOS apps rely on snapshot tests and we use a set of Expecta matchers for Specta that DB wrote. However, we weren’t using Specta for Eidolon and the matchers we were using wouldn’t work, so I wrote some new ones. This was great from my perspective, since I didn’t really understand how the under-the-hood of a unit testing framework worked until I wrote the new matchers. It’s been fun and educational to see Quick and Nimble grow as projects. As an early adopter, the Artsy iOS team has been able to provide feedback on its development. This has hopefully helped Quick and Nimble grow in ways that benefitted from real-world use, but by contributing to the project, it also helped us get features we needed faster (you can insert either a “quick” or “swift” pun here as you wish).

As I neared the beginning of development work on Eidolon, Orta and I discussed how we would want our networking layer to operate. One our our first GitHub issues enumerated the desired features of our new network layer. In summary:

- Make it easy to run the app offline

- Treat stubs as a first class citizens

- Allow tests to state that only networking request X is allowed during this test run

- Keep track of current requests and don’t support dupes

These features grew mainly out of frustrations with our ad hoc approach to network testing on our other projects: some tests would rely on stubbed models with populated data while other tests would rely on stubbed network responses.

The result of these conversations was Moya, a networking library that takes advantage of some really cool features in Swift. With some help from Chris Eidhof, we were able to write a functional-esque network abstraction library on top of Alamofire that provided compile-time checking for API endpoints. I even wrote an optional ReactiveCocoa-based interface for Moya. This interface does not accept callback closures; instead, it returns a signal that represents the network request. Following ReactiveCocoa best-practices, this signal is cold, meaning that until someone subscribes to it (that is, registers their interest in the network request), the request is not fetched. We were even able to write a check for duplicate, in-flight requests and return existing signals.

Combined with the optional ReactiveCocoa extensions, Moya succeeded in addressing all of our needs for Eidolon’s network layer. Additionally, as each project matured, the needs of a full app informed the design and development of Moya.

One final component that had to be addressed before main development could get underway was the issue of API keys. We wanted to have our app accessible to anyone who was interested in it, but limit access to our API keys. Keeping keys secure when they are stored near source code is closely related to the problem of keeping keys secure once an app is compiled. To quote John Adams, a member of the Twitter Security Team:

Putting this in the context of, “should you be storing keys in software”, is more appropriate. Many companies do this. It’s never a good idea.

Over the course of a few weeks, Orta solicited some help from CocoaPods contributor Samuel Giddins to create cocoapods-keys. This project is a CocoaPods plugin that stores the names of the keys you want to use in a plaintext file in your ~/.cocoapods directory. The values of the keys with matching names are stored securely in your OS X keychain. Whenever you run pod install, this plugin generates an obfuscated char array with all of your applications keys mixed up with some other random data. The keys are only un-scrambled at runtime, and the file is ignored by git. Every developer on our team has their own API keys that are stored in their OS X keychains, far away from any git repository. While using this technique by no means guarantees the security of your API keys (a dedicated hacker with a debugger attached to your running app would still be able to retrieve your keys), it’s better than nothing.

We began main work on the project. Orta and I divided the app into two pieces: auction listings and bid fulfillment. We created two separate storyboards that would each encapsulate one of these app components. Orta took fulfillment and I took listings – over the course of Eidolon’s development, we had very few merge conflicts.

We used SBConstants to have compile-time safety when referring to storyboard identifiers and we used Swift’s operator overloading to make using these constants really easy. For example:

override func prepareForSegue(segue: UIStoryboardSegue, sender: AnyObject?) {

if segue == .LoadAdminWebViewController {

// code goes here

}

}

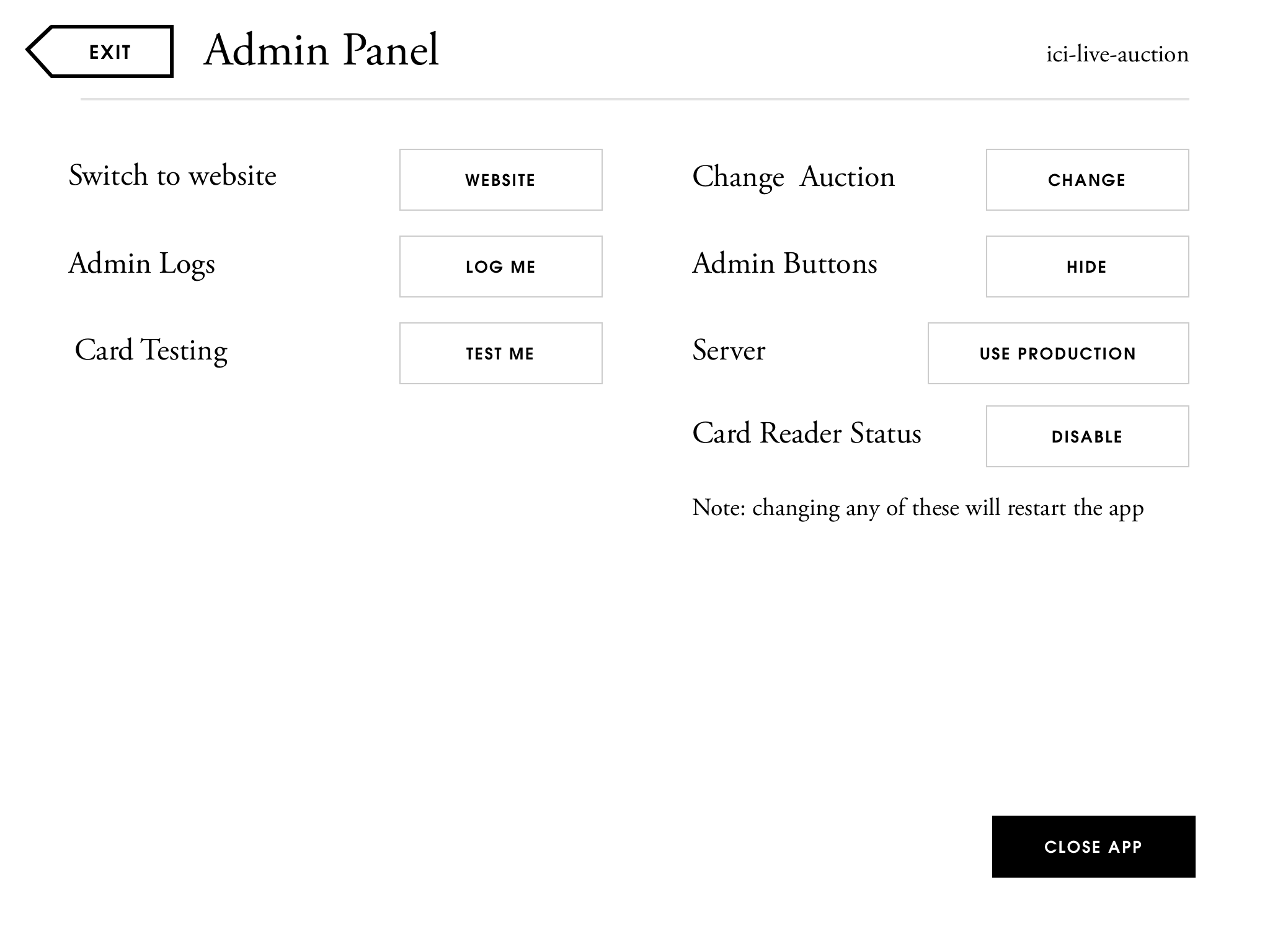

A component that I had not developed before was an admin panel that Orta made. This panel is accessible via a hard-to-accidentally-invoke gesture within the app and is protected by a password to prevent users from accidentally accessing it. The admin panel lets you change core behaviours of the app without recompiling it. For example, the panel is used to change between production and staging.

Speaking of production and staging, to prevent developers from accidentally placing bids on production and to prevent live users from inadvertently using the staging servers, Orta made a simple badge that would let you know if you were on staging. If you were running in the simulator, it would also alert you if you were running on production. This was great, but wouldn’t prevent someone from accidentally placing bids on the production server while testing on a device. Our solution was to check your current wifi network name. If it looks like you’re at the Artsy offices, then the production flag is shown, even on a device.

So we’ve got the scaffolding for a great app and it was time to really begin development. Using ReactiveCocoa, we were able to make our XApp authentication transparent. Functional reactive programming had other great benefits, like scheduling automated refreshes of auction listings. We may have gone overboard in one instance (cleaning that up is on my todo list), but ReactiveCocoa has made modelling complex behaviour of Eidolon relatively easy.

Of course, learning how to ReactiveCocoa is no easy feat. At this point, Orta and Laura were both working on Eidolon. There were many conversations in our Slack chatroom about how to approach problem-solving the ReactiveCocoa way and, with some time, they both became proficient at creating and manipulating signals. Sweet.

I’ve often been asked by people who want to use ReactiveCocoa about how to get their team up to speed; until recently, I didn’t have an answer. Now that I’ve done it, I can say that the most important thing is that you realize that you’re going to be responsible for this decision. If another developer needs help using ReactiveCocoa, you’ll be the one that helps them, so take that into consideration when scheduling your work. There were also several occasions where I didn’t know the answers to the questions Orta and Laura had, but the ReactiveCocoa community was there to support us.

So what about Swift? I mean, there are other apps out there for iOS 8 and other apps that use ReactiveCocoa – how did we find Swift?

Well, at first it was great. We took our own approach to it, trying out new language features that were unavailable to us in Objective-C. We even did away with the usual comment header that Xcode includes in newly created files – what is that even for?

Progress was slow at first, but Orta and I (Laura was not yet on the project) assumed that was due to our unfamiliarity with the language. Eventually, we became relatively proficient, but our progress was still really slow. Why?

However ready you think the Swift language is (and however much you believe Apple’s PR about the language), the reality is that the tools necessary to use Swift are far from ready. During the Xcode 6 betas, we stayed up-to-date in the hopes that newer versions of Xcode would fix our problems. However, after the GMs were released, it became apparent that these problems would just be a reality of working in Swift.

What kind of problems? Certainly there were Xcode crashes, but those were mostly fixed by beta 5. Building the app with enterprise distribution certificates cost us a few days of headaches, sure. And we still can’t compile the app with compiler optimizations without causing a segfault. But what really became the bane of our existence were SourceKit crashes.

When SourceKit crashes, you temporarily lose autocomplete, syntax highlighting, and the behaviour of the text editor’s shortcut keys changes dramatically. The larger your project, the more often SourceKit crashes. These crashes can last anywhere from a split second to ten seconds or more and can be alleviated using an array of cargo-cult techniques such as:

- deleting your derived data folder

- restarting Xcode

- restarting your computer

- restarting the project from scratch using Objective-C

It’s really too bad. I’ve been asking for a replacement to Objective-C for a while and, when Swift was announced, I was ecstatic. However, based on our experience using Swift in a full production app, it is our conclusion that Swift is not yet ready for use in production apps unless you are willing to take on unknown risks and delays. As much as I want to like Swift, I can’t make the recommendation that you should use it, even if that’s what I’d like to say. I think that Steve Streza put it best:

Objective-C in the streets, Swift in the sheets.

— Steve Streza (@SteveStreza) June 4, 2014As we neared our deadline, we realized that we probably weren’t going to make it. This was despite Katarina dropping some features from the “must-have” list. Orta sent out an email to the auctions team letting them know the bad news and we looked at alternatives; none of them suited us. Through some late nights and weekends, and a lot of coffee and tea, the three of us were able to complete the project with only a few hours to spare. It was a herculean effort and I’m incredibly proud to have worked with Orta and Laura to make it a success.

The launch went fairly smoothly, with Orta on-site to assist if necessary. The auction attendees found the software easy to use – one even said that the app made bidding “too easy”, which we are incredibly proud of.

However, this successful launch came at a cost. It was only through some very long hours and a disregard for code longevity that we were able to complete the project on time. Ignoring unit tests was fine at the time, but we now have significant technical debt that we’ll be spending the next few weeks repaying.

Lessons Learned

It is completely possible to write an open source iOS application, though we did have to create some tools to help us along the way. These tools are now available for everyone to use, so you should consider opening your next project from the start. We’ve adopted an “open by default” approach where we only keep things closed when we have to, like with our fonts which have restrictive licenses. If your next app isn’t a core part of what makes you you, consider having a conversation about the pros and cons of making it open source.

ReactiveCocoa is really great at networking. It forced us to use some good abstractions that we might have otherwise cut corners on. Orta describes complex signal mapping to be “too magic.” For example, you can probably figure out what the following line of code does:

RAC(self, "artworks") <~ XAppRequest(.Artworks(auctionID)).filterSuccessfulStatusCodes().mapJSON().catch { (error) -> RACSignal! in

println("Error: \(error)")

return RACSignal.empty()

}

Grab some artworks with the auction ID, filter out non-successful status codes, turn the data into JSON, and if anything goes wrong with any of that, log the error and ignore the results. Then bind the result of that operation to the artworks property of self. Nice and easy.

We discovered, as I mentioned earlier, that Swift just isn’t ready for primetime yet. I want it to be, but it was probably a mistake to write the app in Swift. By our projections, it took us about four times longer than we had anticipated to complete the project (in terms of person-hours worked). A lot of that is admittedly due to our own faulty estimates, but a lot more of it is attributable to Swift’s immaturity. In future projects, we’re going to be more mindful about estimation.

So What Now?

Swift isn’t ready yet, but we already have an app written in Swift, so what do we do? We could rewrite the whole app in Objective-C, but that would represent a substantial effort with very little reward, considering that the tools surrounding Swift are expected to improve over the coming months and years. We could shift away from Swift, writing all new code in Objective-C, but a lot of the app relies on existing Swift idioms, like Moya’s compile-time safety of API endpoint checking.

So we’re pretty much stuck with Swift, as much as you can be “stuck” with a totally awesome language that just needs some more time to have a mature ecosystem of tools. Swift does, after all, address most of my concerns with Objective-C. It has a lot of features that made developing Eidolon a joy. I’m impressed with what Apple’s made so far, but I’m eagerly waiting for Xcode 6.2 and beyond.

On our other iOS projects, we’ll stick with Objective-C for now, but we’re starting to have conversations around what would be necessary to move to developing those in the open, too. In that respect, Eidolon has been an unqualified success.

Comments